Of all the off-kilter classics Omnipollo has given the world Yellow Belly is likely the best known. As a gypsy brewer with no large-scale facility of its own, Omnipollo is a collaborator by necessity as well as inclination, and on this brew they partnered with the UK’s Buxton Brewery. The result is a ‘peanut butter biscuit stout’ that arrives dressed like a Klansman. If that combination of flavours in a beer seems a little outré to you, don’t be put off: this is ‘a peanut butter biscuit stout with no biscuits, butter or nuts’. (One wonders if they tried to find a way to make it a non-stout as well). And if the packaging seems a little … off, needless to say it’s no more what it seems than the beer. Remove the paper wrapping with its twisted top, typewriter-font and pair of wide black eyes and you’ll find more text, denouncing the anonymity and cowardliness that underpin racism and bigotry.

I’ve used Yellow Belly as an example here to show that, while Omnipollo has plenty in common with the other shining lights of the brewing community, it tends to take things further, both in terms of flavour-combinations and in how the resulting beers are presented. Indeed, testifying to the seriousness with which they take the packaging of their products, from the ground up Omnipollo is a collaboration between brewer Henok Fentie and designer/artist Karl Grandin. Talking to the latter, it becomes clear that trying to say which comes first in Omnipollo-world is antithetical to the entire endeavour.

“We work independently,” he tells me. “Henok is in charge of the brewing and I do the design. But on the other hand we constantly discuss ideas, names, concepts and expressions. So the two aspects feed off each other: a recipe of Henok’s might be initially suggested by a design concept of mine, or it could be the other way around. It’s a collaboration across the board. In fact, the book we did together in 2013 [‘Brygg öl’, Swedish for ‘Brew Beer’] is more or less a document of Henok teaching me how to brew in his kitchen …”

So they take the packaging of their brews very seriously indeed. Further, as Yellow Belly suggests, Grandin isn’t shy of using it to address serious political issues. Other designs incorporate wittily defaced currency and elements suggesting crescent moons and Stars of David——never unfraught icons, and never less so than today. Does he intentionally insert his work into these sorts of charged political areas?

“When I was a kid, my dad hung a framed postcard over my bed that showed the famous devil from the Codex Gigas. I’d spend hours just staring at it. But at the same time, I was paying attention to the wallpaper behind it, a ‘70s-style medallion pattern.”

Installation view from The Omnipollo at Kuvva Gallery in Amsterdam, 2014.

“Well, a design is a kind of a story——that’s how I look at it. And many of the stories I create, or insinuate, in my images are based on things that I see around me. We live in a world where political and religious symbols are everywhere, and they’re charged and at the same time constantly changeable, which is a huge influence in my work. There is always an element of meaning in my images and that means there’s also a political aspect to them. There’s no way around it.”

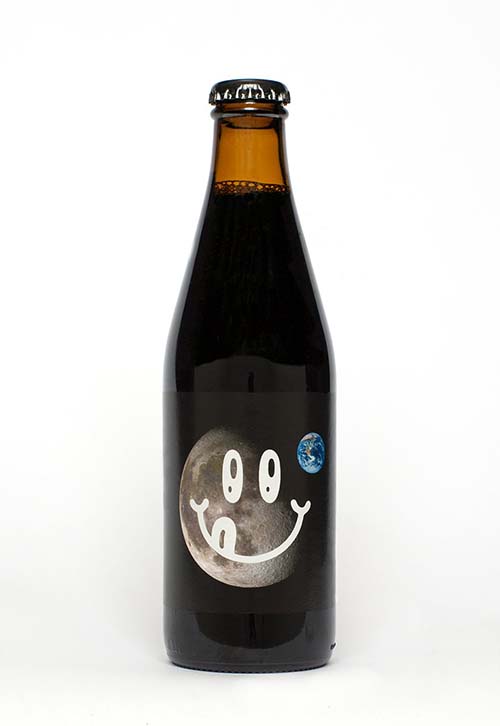

In fact, and not unrelatedly, he seems interested in religion in general. Those crescent moons and Stars of David appear in a tee-shirt and handkerchief collection——titled Conspiracy——he produced in collaboration with Chickenshit Conspiracy and Save Your Nossse, and the meeting of pop-culture and piety is a common motif. In a 2014 show at Amsterdam’s Kuvva Gallery there were candles mounted in beer-bottles circling pillars, giving the room a votive feel, and there’s an Omnipollo beer entitled Nebuchadnezzar.

Nebuchadnezzar

When I ask him about this he replies with an anecdote. It turns out the meeting of the religious and the kitsch (for want of a better word) goes right to the heart of his work.

“When I was a kid, my dad hung a framed postcard over my bed that showed the famous devil from the Codex Gigas.” (The largest medieval manuscript to survive, the codex is said to have been produced by a monk who’d sold his soul to Satan. The famous illustration it contains of the devil has led to its nickname ‘the Devil’s Manuscript’.) “I was spellbound: it was the most amazing thing I’d ever seen and I’d spend hours just staring at it. But at the same time, I was paying attention to the wallpaper behind it, a ‘70s-style medallion pattern that’s stayed with me equally. Just as much as the devil, that pattern seemed to have a huge amount to say, to contain a code for me to decipher. For me they existed on the same plane of existence.”

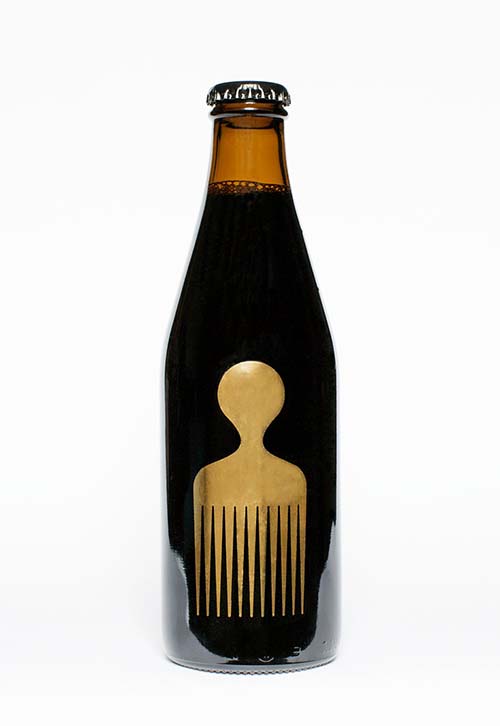

Omnipollo’s myriad offbeat artworks.

This kind of collapsing of the difference between disparate registers and aesthetics is characteristic of Karl Grandin’s designs, which constantly conflate styles in the process of constructing their quirky, arresting little stories. Vivid symbols sit strikingly yet comfortably alongside charming twentieth-century period details and flashes of humour, so that to an unusual degree the designs—as Grandin says he hopes they would—are able to appeal to the unconscious as well as the eye.

“I’m always trying to appeal to the unconscious, in the Jungian sense of the word. In fact, I’m interested in appealing to the collective unconscious, to a sort of shared memory and language of the imagination that all people and cultures share. I try to access that in my work. It was particularly true of two recent sculptural installation pieces, Kosmogonen and Gudmaskinen, where I blended religious symbols and cosmological models with elements from mythology, fantasy, fairy tales and other fantastical stories of weirdness …”

Grandin is also constantly trying to find new ways to look at the familiar, the outmoded or the hackneyed. This might seem like trendy postmodernism, but in fact Grandin’s approach is much more constructive than deconstructive: rather than emphasising the tiredness of old tropes, he sees the work as an opportunity to revitalise and refresh them by revealing them in a new light from a new perspective. It’s a process of regeneration-by-appropriation, which brings me to a tricky question.

A little cautiously, I ask him about the Yellow Belly package. In the era of President Trump (which remains an extraordinary thing to type), a resurgent white supremacist movement and Black Lives Matter, it clearly couldn’t be more topical. But as the Kendall Jenner Pepsi commercial controversy demonstrated in extremis, it can be risky for commercial concerns to wander into these sorts of debate.

Gudmaskinen installation at Hobo Hotel, Stockholm.

Karl Grandin and Gustav Karlsson Frost, Marble.

The label for Omnipollo’s Gone, which adds a ‘G’ to the ‘One’ on a dollar-bill, wittily raises an acerbic eyebrow towards economic inequality and dysfunction and seems safe-if-cheeky. But a bottle that looks like a Klansman? Racial inequality seems rather a fraught issue for a brewer trying to sell fancy drinks.

“Sure,” he responds. “Of course there will always be people who disagree with you, or the risk of offending someone. But we’re not just trying to selling fancy drinks. We don’t look at Omnipollo as just a business or the products as just products. The products are our art, and so of course they express our personalities and what we’re thinking about, what we’re feeling. Look at the description of Yellow Belly: the packaging isn’t just a little visual joke, we’re expressing our whole ethos and declaring ourselves against what we see as contemporary evils.” He pauses. “Of course there will always be people that disagree with you——such is art. But I also do not aim to please everyone.”

He does not: that much is clear from the determinedly quirky quality of much of the work. Given that, I wonder how much he chafes against the limitations of working in a commercial environment where, in the end, whatever else the work does it has to package a beer. But it turns out not at all.

“We don’t look at Omnipollo as just a business or the products as just products. The products are our art.”

“No,” he says, “packaging and design have always fascinated me. I don’t really see it as a limitation but an opportunity——or maybe the limitation is an opportunity. Plus, the way that Omnipollo works——brewing all over the world with different breweries and conditions and so many different types of bottles and cans and containers——means that it’s hardly limiting. There isn’t really a unifying format at all, and we don’t bother with logos or branding, so the freedom is actually pretty considerable.”

Omnipollo, obviously, is a lot more than just a brewer—or, rather, Omnipollo demonstrates that a brewer can be a lot more than we might usually assume possible. In fact, Henok Fentie and Karl Grandin’s combination of surprising, delicious beers and bold, fun, striking packaging leave most of Omnipollo’s competition looking a little——dare I say it——yellow-bellied. Long may they lead the field for drinkers as interested in art as beer.