Chapter One: Nostalgia.

Germans have all the best words. Registering on the mainstream scale we’ve got schadenfreude, which sits snugly inside English dictionaries as a loanword, then for the German language hipsters, we have: fremdschämen. A real treat, this one; an untranslatable word that describes the sensation of feeling ashamed about something somebody else has done. (Think of it as the title for a German-dubbed version of Curb Your Enthusiasm.) And on the romanticists’ side of the spectrum is fernweh: literally ‘farsickness’, a kind of counter to homesickness that defines a longing for somewhere far away. Particularly so, somewhere you are yet to visit.

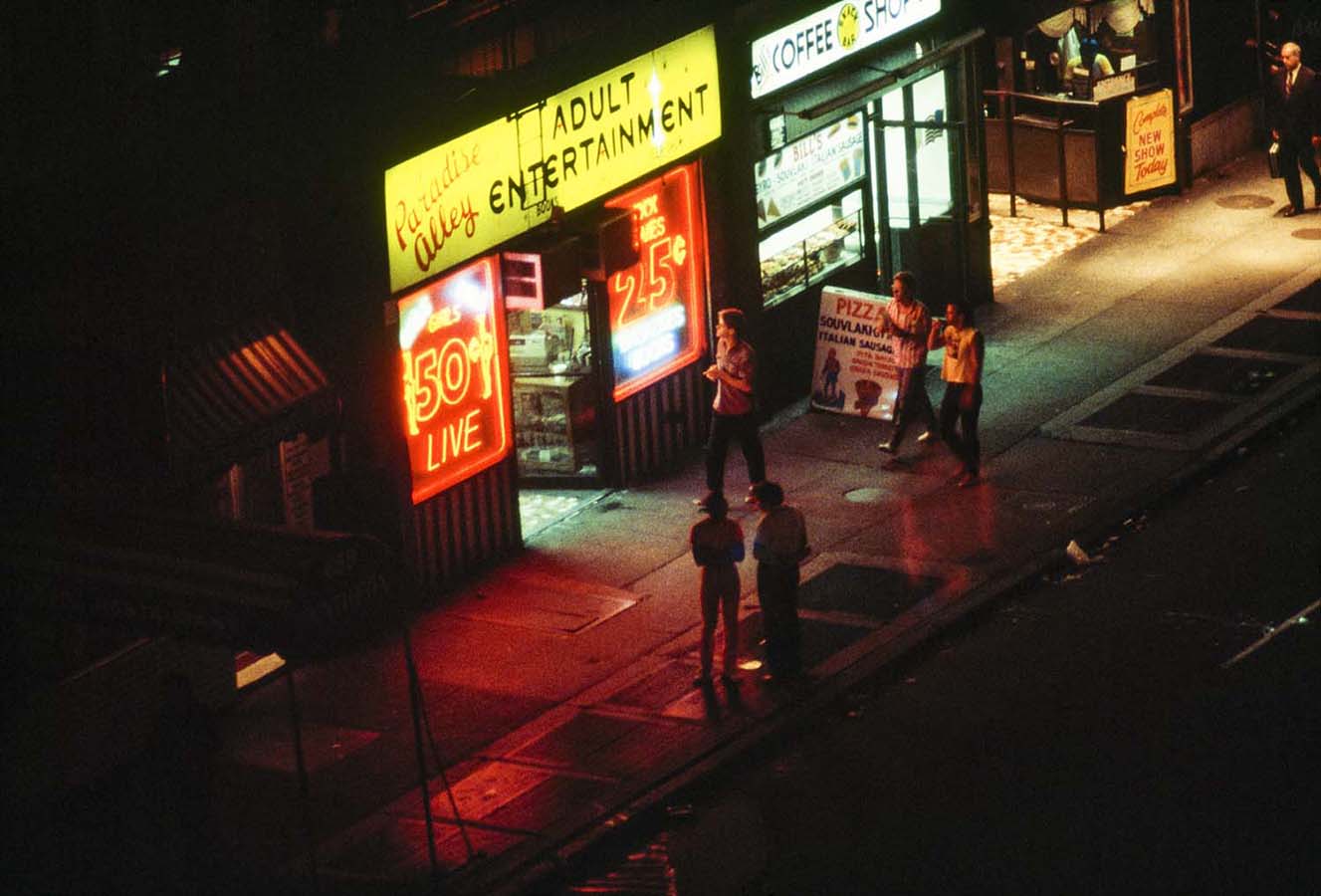

My fernweh is for late-1970s, early ‘80s New York. It’s a scratch that I will never truly itch, but a ‘farsickness’ I have long tried to sate. I saw the cult 1980 teen drama, Times Square, at some point in my formative years, I poured over stories of no-go areas and sleaziness on every street corner. (I was an odd kid.)

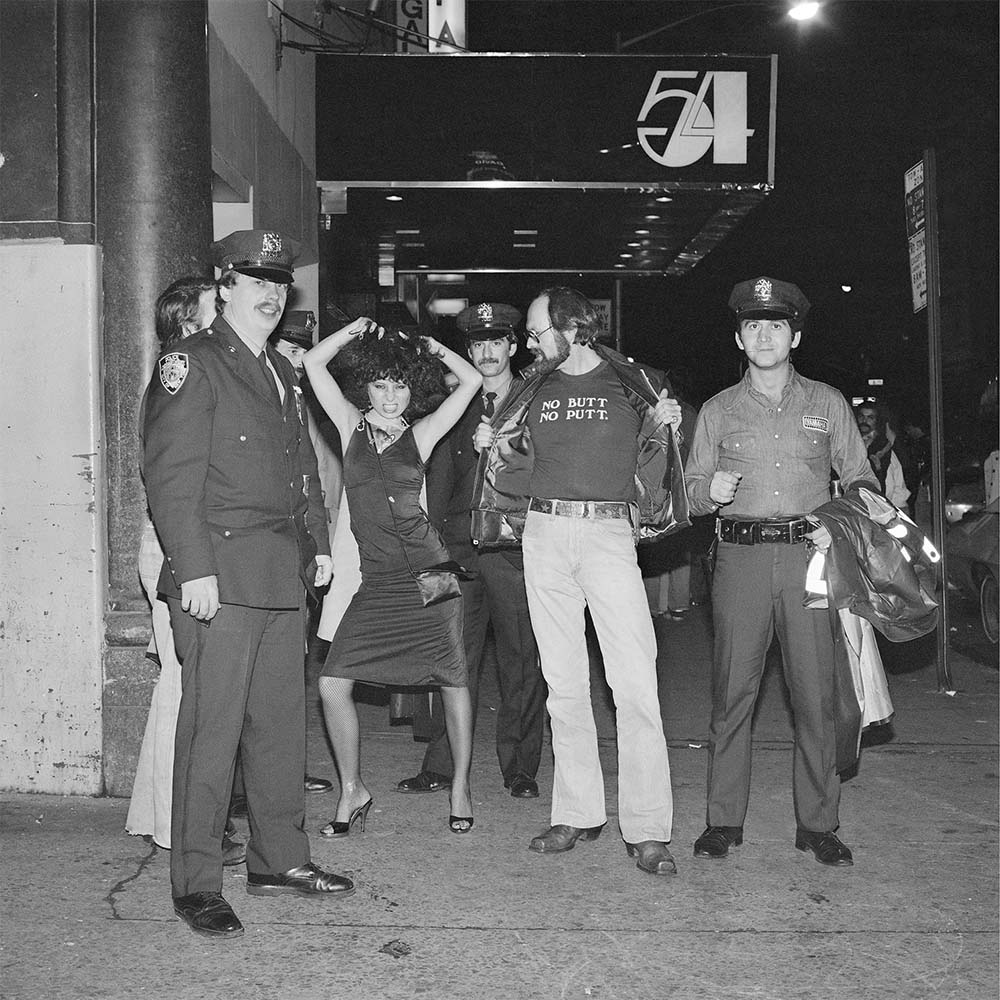

Rejected From Studio 54 No No

Studio 54, NY, NY, October 1978

© Meryl Meisler.

© Jane Dickson.

Later I would become obsessed with underground disco music and its coalescence with post-punk new wave. Russell, Levan, Gibbons, Kevorkian, Krivit, Mancuso, Byrne, Reed and Cale, Vega and Rev. The genesis of hip hop and of street art. I began to study intently the photography of Arlene Gottfried, Richard Sandler, Meryl Meisler, Miron Zownir; marvelled the peep show paintings of Jane Dickson. My favourite artists are Warhol, Haring and Basquiat. I’ve got it bad.

But New York is one of those cities, isn’t it? You know it long before the first time you ever go. It emotes nostalgia at every turn. The movies, the photos, the pop stars and their songs. It has a familiarity to the unfamiliar.

Carroll Gardens is the sort of Brooklyn neighbourhood that conjures this exact sensation. Leafy and lined with brownstones, calm and slow with Italian American heritage. It’s where the good guys live in heartfelt movies about firefighters and coming of age. It is, too, where an unassuming beer brand live, one that is yet to achieve the sort of social media clout fellow New Yorkers such as Other Half or Finback have enjoyed over the Atlantic.

There’s a soothing sense of the nostalgic about everything at Folksbier.

Ambling down an innocuous residential street with an old iPhone devoid of data roaming and whose battery is about to pack in, I briefly fear the brewery-taproom of Folksbier may be a step too unassuming. Thankfully found, and with founder Travis Kauffman sitting me down with a pint of O.B.L. (Old Bavarian Lager), you quickly realise that unassuming is the point. It’s key to the modus operandi around here.

Founder Travis Kauffman pours me a pint of O.B.L. (Old Bavarian Lager), and all that is unassuming about Folksbier begins to make sense.

Kauffman is warm and inviting. Clearly intelligent and studious, with a look somewhere between geography teacher and bass player from a flannel-clad band like The National. Softly spoken, but with purpose. Growing up on a farm in Michigan, the mantras ingrained in him as a child are evident in his approach to beer. And that studiousness has seen him hone German-style recipes with a resolute emphasis upon the clean, the crisp, and the drinkable.

A rustic space that you feel evokes Travis’s nostalgia for sleepy farmhouses and an expanse of nature, the taproom feeds into the concept here. Nothing feels rushed, a decrepit ‘house number and transit map’ of the five boroughs brings minimal colour to a white-washed concrete wall, odd-sods of wooden furniture below. The bar area is all wooden panelling in kitsch cabin style; cans dressed in unfussy labels line a shelf above the till. There’s an IPA among them, a double at that, but the line-up is more notable for pilsners and lagers, a weizen beer, and a range of Berliner weisse-style beers named Glow Up.

Kauffman brings over a couple of wine glasses and the green yuzu version of the latter. It’s sublime. As crisp and clean and as drinkable a beer as you could want. He talks with passion about beers of this profile, his fondness for the German Reinheitsgebot, but too makes a point of telling me he’s not rubbishing modern IPAs and their ilk. This is not beer snobbery, you just feel that Travis genuinely adores producing beers that speak to him.

It’s my first time in New York since 2014, when I spent the best part of a month staying on Bedford Ave, Williamsburg. I’ve only been here a couple of days, but the landscape of craft beer in the city has since changed dramatically.

Folksbier’s Green Yuzu Glow Up; as crisp and clean and as drinkable a beer as you’d want.

I’ve noted——and drank, of course I’ve drank——fresh cans from Instagram-famous breweries such as Barrier Brewing, Evil Twin NYC, Grimm Artisanal Ales and KCBC. All at $4.99 a pop lining the shelves of fridges at corner shop bodegas and Whole Foods. (Thats five dollars and a cent to show, my European friends.) New breweries and taprooms are popping up by the week. Our conversation shifts toward as to why.

On that last visit I was just as agape as I had always been visiting the U.S. Agape at the penetration into the mainstream craft beer enjoys; agape at being able to drink classic standards from breweries like New Belgium or Dogfish Head at any corner bar; agape at the ability to stock my fridge with cheap and excellent cans of resinous, bitter IPAs. I did not, however, realise the city was on the cusp of momentous change.

In the December of that year——the 13th, at 15:16 (and seven seconds) to be precise——a critical piece of legislation would pass. Allowing the sale of beer on brewery premises, the lowering of minimum food requirements, and an increased production cap, naturally Kauffman cites the Craft New York Act as a game-changer in the city’s beer scene. You may not know the legislation, but you know its legacy. You’ve double-tapped it a million times.

The five years that changed craft beer in New York are the same five years that changed craft beer the world over.

In a decade whose rhythm was dictated by social media, Instagram’s influence was profound. First on celebrity, then on posturing influencers with tormented Instagram husbands; next food conceived for likes over flavour, and brunch. Fucking brunch. Interior design briefs began and ended with ‘Instagrammable’, and contemporary artists started considering the ‘Gram before traditional notions of space or the self. It was just a matter of time before it transformed beer beyond recognition.

Fresh cans from renowned breweries such as Barrier Brewing, Grimm Artisanal Ales, Threes and KCBC line the shelves of fridges at corner shop bodegas at $4.99 a pop.

In tandem with the rise of new breweries and taprooms across the five boroughs was the ascendency of #craftnotcrap and the dawn of ‘joose’ ubiquity, and many of its big names were beneficiaries of their state’s craft act. LIC Beer Project, Barrier, Interboro, Finback, KCBC, Other Half——names that flooded Instagram with the sort of prestige and status we automatically afford to American brewers by way of their craft heritage. For the latter, people would camp in queues for can releases; Europeans would pay upwards of a tenner for the rare few 440s that made it across the Atlantic. They would become stars of the scene.

The five years that changed craft beer in New York are the same five years that changed craft beer the world over. We exist in what marketers refer to as the the ‘global village’. In 2014, I arrived in New York having spent three months in Melbourne. Coffee shops had eerily familiar aesthetics, the wave of cultural gentrification had become the new norm. Instagram confirmed homogenisation as the new counterculture; its global appeal vanilla-washing our world. In late 2019 I arrive again on the crest of a new similitude. NEIPA is the new flat white. Discuss. Repeat.

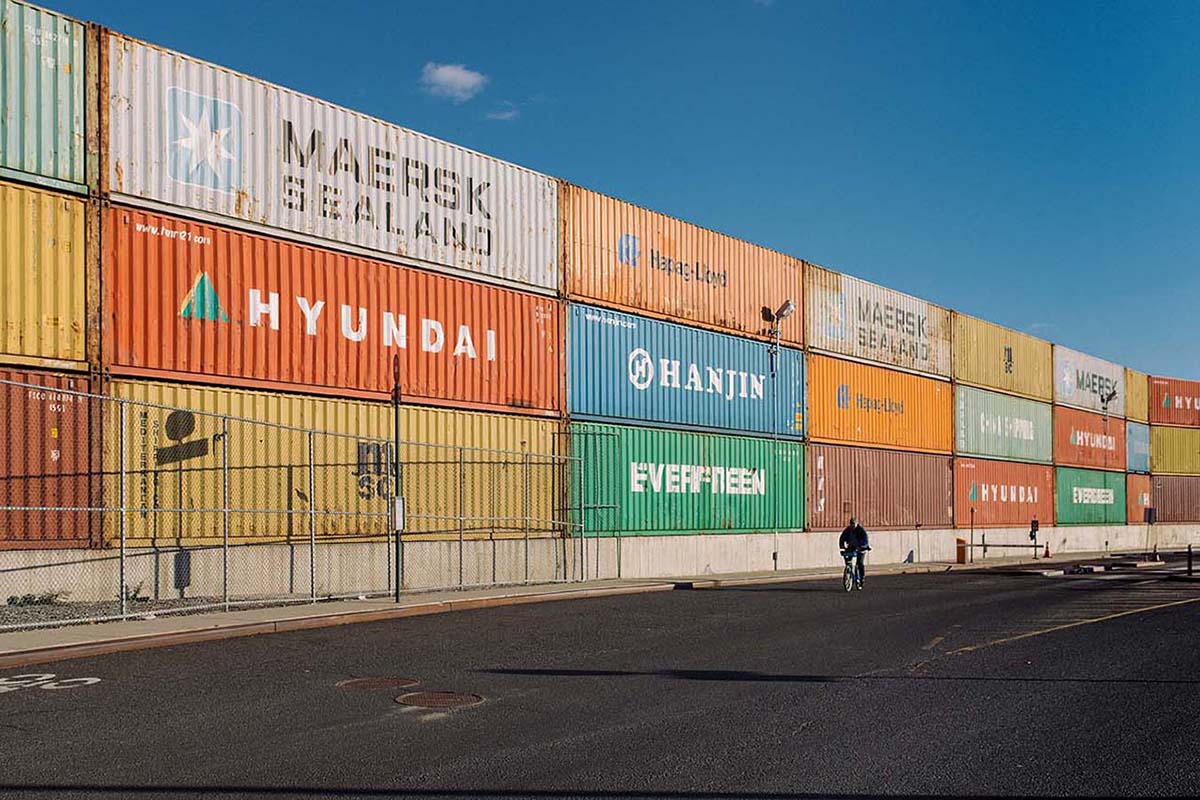

Which takes us back to sleepy Carroll Gardens and its streets paved with blue collar graft. Folksbier is a speedy five minute walk from another brewery on my list, so I set out. Five minutes that seem a million miles. You quickly find yourself in the shadow of the decaying I-278, its lanes of traffic rattling through the ageing steel supports of an expressway constructed across a disused elevated railway in 1939. It’s not an area of Thanksgiving celebrations or Sunday afternoon barbecues, rather crumbling industry, rust, white vans and McDonalds drive through.

We are in Gowanus. It’s the Brooklyn of warehouses, dilapidation and shady deals, a very different kind of nostalgia. But nostalgic nonetheless. It has an air of the up-and-not-coming-for-an-awfully-long-time about it. But New York retains its energy in even the most shabby of settings. More so with my bad case of fernweh. Scrap metal yards and concrete factories, a canal famously polluted with toxic chemicals. Noisy and frayed around the edges it may be, but that short walk has taken us to the spiritual home of beer hype.

The Other Half taproom, Gowanus.

These are the streets you’ve seen portable chairs line up on the night before a can release; the warehouse you’ve seen gleeful Untappd fanatics exiting, arms full with crates of brightly coloured cans. It’s the land of the NEIPA and the DIPA. It is home to Other Half Brewing Company.

Other Half’s Pumpkin Spice Crunchee; DDH oh…Forever 8% imperial IPA; and a guest beer from The Veil, Lil BB’s Brekkie Tastee.

Packed pallets and steel kegs line the streets, it seems an entire block of this industrial wasteland has been overrun by the beer brand who made the hazy IPA their own. It’s just 13:30 on a weekday, but there is a buzz about the place. Those military-grade trucks that Americans like to drive pull up to snatch cans fresh off the line, all manner of beer fans are here; taking selfies in the taproom or thrusting fresh green notes at the shop staff. Hockey fans, latinos in NFL shirts with jawlines as strong as a double figure ABV DIPA, beer tourists, middle-aged couples.

I order 4oz tasters of Pumpkin Spice Crunchee, a 7.4% imperial granola Berliner weisse brewed with pumpkins, almonds, pecans, cinnamon, maple syrup, vanilla, coconut and lactose; the DDH oh…Forever 8% imperial IPA; and a guest beer from The Veil, Lil BB’s Brekkie Tastee, a 5.5% smoothie-style sour ale brewed with lactose, oats, maple syrup, strawberry, banana and blueberry. There’s a violence in the speed with which a man at the bar is tapping the screen of his iPhone, blasting space invaders in a fraught metaphor for the fervour that quickly becomes you here.

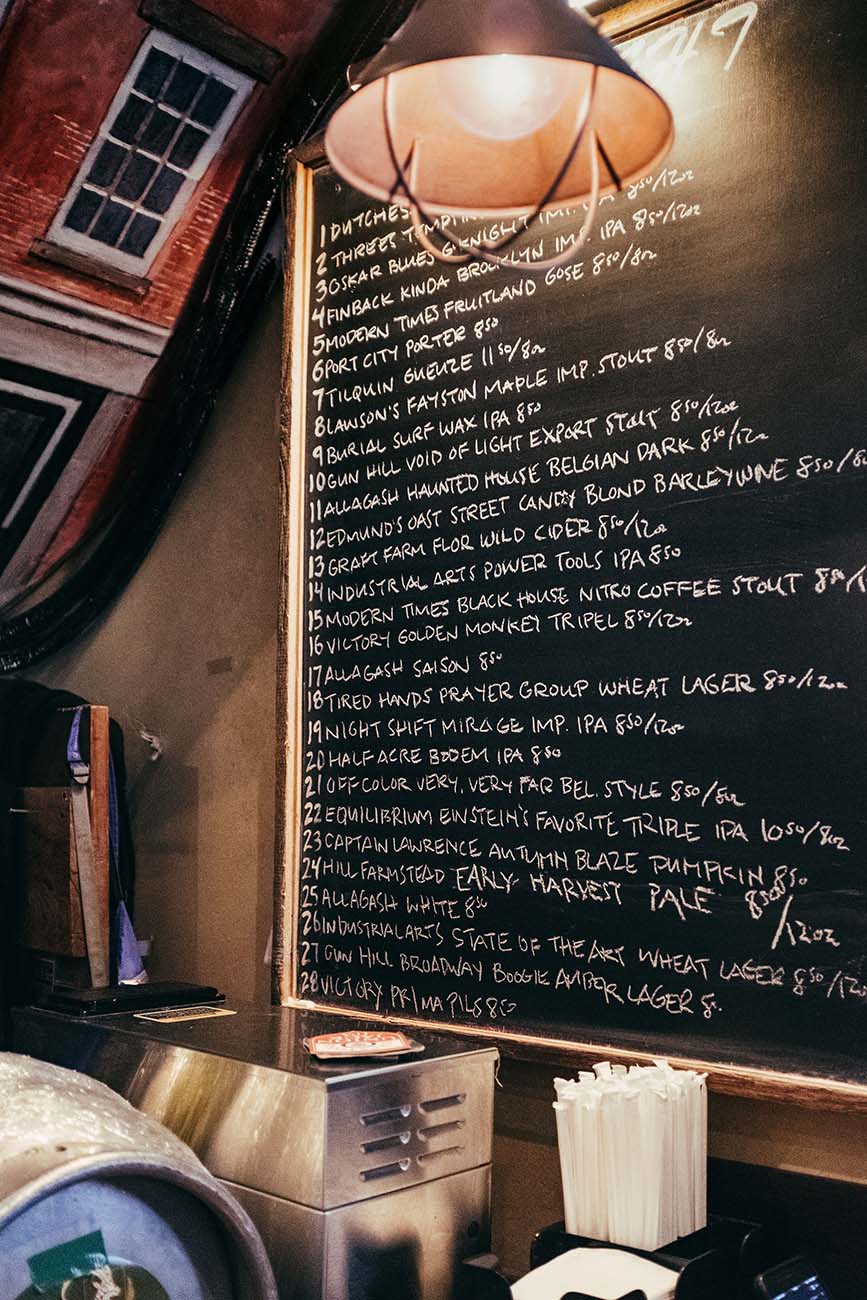

Beer rolls straight from the tanks into the back of Ford F-150s. Other Half are printing money. The taproom has a nice industrial cool to it, technicolour names are chalked onto a blackboard behind the bar. It’s full of life. The excitement you’ve been led to expect is here. It’s an enjoyable experience. But these beers, which could set Instagram and Untappd alight, are sickly and sweet in comparison to the crisp serenity of the Green Yuzu Glow Up. My nostalgia turns to a yearning for Folksbier.

Anyway, point is, this juxtaposition is the quintessential issue with contemporary beer culture. “Craft beer consumers scroll and double-tap now,” writes Chris Hall in an excellent article on maturity (or lack of) in the scene, “There’s no time to type, or respond, or think.” The most important thing here is the speed with which we are hit by hype and haze and hysteria. There is a sense that we are liking beers before we have tasted them. Instagram has daubed a Dalíesque distortion on our world, and beer is as susceptible to that as a ‘candid’ shot hours in the making.

The most important thing here is the speed with which we are hit by hype and haze and hysteria. There is a sense that we are liking beers before we have tasted them.

As an image of the Manhattan skyline does not capture the guy in a wheelchair who lives on a traffic island in the Lower East Side and screams orders at pedestrians, an image of hazy liquid cannot be tasted. “Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real,” muses Jean Baudrillard in his essay, Simulacra and Simulation, “when in fact all of Los Angeles and the America surrounding it are no longer real, but of the order of the hyper-real and of simulation.”

The French philosopher foresaw the post-text future in the early 1980s. In Instagram as a simulacrum, seeing is not believing.

Paulie Gee’s Slice Shop, Greenpoint.

Chapter Two: Pizza.

Pizza is one of those things that shouldn’t be fucked around with. I’ve eaten a good pizza in Rome, once, but on the whole even the majority of Italians don’t really seem to get it. If pizza is simply a category on a wider menu, then avoid it at all costs. It should not be thin and crispy, nor should it not be fat and indigestible. It should never, ever ever, be frozen. If you’re going to bother doing something, do it well. Follow the Neapolitan way. Make it light and airy, blistered with intense heat, and fuss-free. That said, there is one exception to this rule.

New York pizza. It’s a thing of rare beauty. Dished up in slices that alone could see you through the day, their dense and charred dough just rough enough to give the roof of your mouth that satisfying tingle. As can the spice. Weighty and substantial, this is a pizza that can take fire and toppings. Oodles of toppings if you so desire. You can get creative in a way that would make Neapolitans volcanically erupt. There is pizza, and then there is New York pizza.

At Paulie Gee’s Slice Shop in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, one will find the Hellboy, a pepperoni ‘pie’ with ‘Mike’s Hot Honey’. It’s sublime, and so too are the surrounds; owner Paul Giannone going in on the vintage look with serious clout. Should you have nostalgia for the 1980s, Formica and wood panelling, then Paulie Gee’s scratches an itch. It is straight out of Stranger Things. The beer, though, thankfully of 21st century America.

It’s a welcome reminder not to get ahead of yourself in denouncing the death of the IPA, not to don your red baseball cap adorned with ‘Make Beer Pils Again’.

Local names like Finback and LIC Beer Project are among the 16 taps dispensing at this pizza joint. (Thats sixteen taps at a pizza slice shop btw.) We opt for a local standard, Other Half’s hazetastic Green City. It goes down a treat, a route one masterclass in NEIPA. It’s a welcome reminder not to get ahead of yourself in denouncing the death of the IPA, not to don your red baseball cap adorned with ‘Make Beer Pils Again’. As one scoffs at gentrification-led homogenisation with their friends over a flat white in a repurposed warehouse, one should be mindful not to rewrite their own beer history. Just enough cognitive dissonance to see us through.

Talking of gentrification, let’s cross the East River.

Dishing out slices to Greenwich Village locals since 1975, Joe’s Pizza embodies the essence of New York street food. It’s quick and abrupt, cheap but brilliant. It’s American in size and style. It is comfort on a paper tray and it tastes so damn good. Loaded with crispy pepperoni and smothered in umami-rich garlic powder, I tuck into it on the square outside; fittingly dedicated to Father Antonio Demo, an Italian-American priest and civic activist. Quick and incredible. It will serve as fuel for an afternoon navigating Manhattan’s beer scene. The next visit? Just one block up Bleecker Street.

Blind Tiger, Greenwich Village.

Opening in 1996, Blind Tiger was a precursor to the onslaught of craft beer in the city and nation at large. Adorned in woods salvaged from a 19th-century farmhouse, it feels like an old British boozer. But better. There’s an almost unnerving number of suits around, but the drinks list soon does away with any concerns about the clientele.

Blind Tiger, Greenwich Village, impresses with 28 draught beers, gravity-dispensed and traditional cask, and countless rare bottles from many of the country’s leading names in craft beer.

28 draught beers. Countless rare bottles. IPAs from Finback, Burial, Half Acre, Equilibrium; a wheat lager from Tired Hands and a pale from Hill Farmstead; there’s even a gravity-dispensed brew from Vermont’s Von Trapp, and a cask German style pilsner from Other Half, which I can’t resist. Nor the Hill Farmstead pale. It’s early afternoon, and leaving now feels like unfinished business.

We head 15 minutes by foot to the Disneyfied foodie festivities at Chelsea Market. It’s packed to the rafters with tourists dragging their heels as if still trying to master the art of one foot in front of the other, but there is great food here, the lines at Los Tacos No.1 move slowly as testament to that. And, being the United States, there’s great beer, but we don’t last long. Cooper’s Craft & Kitchen is nearby, and there’s more serious business to be undertaken.

Aside from an obnoxious bartender who frankly can’t be arsed to walk us through some confusing beer flight pricing, all else here sits well. It is again laced with abundant wood, cosy and supremely stocked. Folksbier’s O.B.L. is here, and a pale from Threes, another Brooklyn brewery who are leading the march of simplicity, but we go for a smoked brown ale from Hill Farmstead; Patter, a saison de coupage with blackberries and grapefruit zest from Grimm; a DIPA by New Jersey’s Magnify Brewing; and Hudson Valley’s Samizdat, a sour IPA with raw wheat and raspberry puree. The latter is exquisite. With basic NEIPAs clogging up the chalkboards of countless European craft beer bars, this really is pig in shit business.

Eduardo Kobra’s Mount Rushmore mural.

Cooper’s Craft & Kitchen, Chelsea.

Once crumbling and commandeered by counterculture, the streets of Manhattan are today like a loading bar stuck eternally on 50%. The cranes and scaffolding a permanence of its aesthetic. And if that loading bar ever hits 100%? An exclusive closed-door playground for the one percent.

515 West 18th Street, Chelsea, is being transformed into a 180-residence luxury condo complex by divisive designer——and cohort of Boris Johnson—— Thomas Heatherwick; the bulging windows he used on a momentous Cape Town grain silo conversion copy and pasted to west Manhattan. Opposite is a commissioned Eduardo Kobra mural of Warhol, Basquiat, Haring and Kahlo. My fernweh should reduce me to tears, but New York’s energy, albeit wildly different today, endures. There pervades a sense of chaos, it is the ultimate metropolis. It can get away with anything.

In Times Square the peep shows and porn shops have gone, in their place Baudrillard’s hyper-real and simulation. New towers are so thin they look like supports to launch civilisation into space. It somehow works. Where Leicester Square is a sort of purgatory you wouldn’t wish on even the worst Fosters drinker, Times Square’s oddness on super-size-me scale is still tinged with a sense of excitement. It somehow works, too. Central Park is no longer a hunting ground for serial killers. Which is good. After all, there are instances when reality can surpass nostalgia.

As Is, Hell’s Kitchen.

There are, however, times when the stars align, when fernweh meets IRL and the two make sweet love. Founded in 2016 by former bartenders from two Michelin-starred Tribeca restaurant, Atera, Hell’s Kitchen’s As Is is a beer bar that dreams are made of. Its interiors are moody, industrial but warm; inviting in a settle in for the afternoon but leave early morning kind of way. I’ve wanted to drink here since the first day I heard about it, and it only over-delivers.

We drink Foam Brewers’ Caribou, a hazy DIPA from the home of the NEIPA; a sour IPA from Little Blind, an excellent small-scale project based in Brooklyn; and a blend of Italian style pils and barrel-aged sour ale from Oxbow.

Too long here is not long enough. And then all of a sudden you’re craving pizza again.

Chapter Three: Experience.

“The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious.”

— Albert Einstein

Now, Bert probably had something more profound in mind when he threw out this poetic pearl of wisdom, but I’ve always found more joy in discovering the obscure or the arcane than I have following a pre-trodden track. I had no idea what Kunsthaus Tacheles was the first time I stumbled upon it, yet the sadly deceased radical Berlin art squat is daubed in indelible squiffiness on my soul. Sometimes I still wake up in a tiny room with five people losing their shit to thundering techno. The echoes of unforgettable times resonate forever.

The mysterious, though, is a concept as equally endangered as the German capital’s iconic squats.

‘Is Instagram ruining travel?’ ‘Is Instagram ruining art?’ ‘Is Instagram ruining our brains?’ ‘Is Instagram destroying humankind?’ All real headlines, all real articles in all real and esteemed publications. Of course we have more to worry about——you know, in that said humankind is destroying the fucking planet, and all——but the concerns exist. In reality, it’s not that Instagram is the one doing the damage, rather our participation with it; something we are all guilty of. From a saved Instagram post to plotting an entry on a ‘to-do’ Google Map. A photo, an IG Story, a virtual ticking off. And on to the next one.

I’m on my fifth day in New York City, and of course some stop-offs have been pre-planned. It’s thought that Greek poet Hesiod (c.700 BC) was the first to get to the crux of it with ‘moderation is best in all things’. He may well have been fond of today’s trend toward low-ABV beers. But as the digital world has aided me in finding a Blind Tiger or an Other Half, it has dealt blows of FOMO in the bars and taprooms time has prevented me from experiencing. Most of all, though, it has been neither use nor ornament to some stand-out moments.

Transmitter Brewing.

Brooklyn Navy Yard.

We can get too caught up on mapping our travels, using apps to streamline and ‘heighten’ our experience, but apps don’t steer you toward off-kilter bedroom-sized dancefloors or dive bars with toilet graffiti older than you. If they do, then they’re probably shit.

The digital world sent me to some lovely places with some lovely beers, it did not send me to a rough-around-the-edges sports bar with decent but mass-produced IPAs for $4 a pop during happy hour (believe me, you’ll quickly swoon for any bargain after a few days here); it did not send me to an awful-but-enigmatic basement dive where the DJ proudly told me it was ‘English music only night’ as he spun a Primal Scream song; it did not send me to the excellent One Mile House, an impossibly dark speakeasy style joint where you lose all sense of time after 17:00, and which has Other Half and Mikkeller NYC brews among its reasonable happy hour offerings. It did not send us to the bar none of us can remember where we belted our hearts out to I Think We’re Alone Now on the jukebox, before being told Tiffany herself had been there just the week prior.

To this extent, Folksbier had existed in a blind zone on my radar, it only coming into range when asking NY beer expert, Cory Smith, for some tips prior to the trip. Via Instagram, of course. Transmitter Brewing was another blip on the radar from Smith, and their light and airy brewpub at Brooklyn Navy Yard’s new food hall is a laidback spot from which to sample some of the equally light and airy brews; their Belgian-inspired farmhouse ales clean, fresh and dangerously drinkable. Two New York breweries with less bombastic profiles in Europe as the likes of Other Half or Barrier, two breweries with less bombastic beers, and all the better for it.

Randolph Beer Williamsburg.

Thanks to social media’s influence on the international craft beer scene, an outsider’s perception may be that New York is a hotbed of Untappd chart toppers, syrupy haze and candy shop adjuncts, but the truth reveals much to the contrary. In Folksbier, Transmitter and Threes, the city has a trio of urban breweries with rural mindsets, breweries capable of stopping you in your tracks with simplicity. In the most important city of the country who gave us the first wave of craft beer, there’s a sense that a new wave is brewing. Crisply, and cleanly.

In Folksbier, Transmitter and Threes, the city has a trio of urban breweries with rural mindsets, breweries capable of stopping you in your tracks with simplicity.

Walking along the front of the East River back toward the heart of Williamsburg, I discover another gem undetected by my Instagram-powered radar. Randolph Beer is not a measly operation, it’s a substantial three-premises business that spans Manhattan and Brooklyn, but across the pond it’s not internet-famous in a way that, say, Tørst (incidentally, just as excellent as it was last time I was here) is. It is also not chin-strokingly cool in a way that, say, Tørst is. Which is not always a bad thing.

Randolph is Brooklyn’s first nanobrewery, an impossibly tight space where head brewer, Flint Whistler, turns its diminutive size to his advantage, experimenting with small-batch brews.

The 24 interactive taps of Randolph’s self-serve ‘Beer ATM’ make for an unexpected experience.

Randolph’s South Williamsburg bar opened in 2013, where they pioneered their self-serve ‘Beer ATM’——24 interactive taps that allow you to pour your own beer, charged by the ounce——but it is fresh from an expansion and remodelling when we arrive. 4,000 square feet, shuffleboard and vintage video games, and the neighbourhood’s first nanobrewery, an impossibly tight space where head brewer, Flint Whistler, turns its diminutive size to his advantage, experimenting on small-batch brews with spices, fruits and vegetables; rare hops and personal yeast concoctions; historical styles and on-site barrel-ageing.

Managing partner, and Certified Cicerone, Kyle Kensrue, speaks enthusiastically about Whistler’s ‘mad scientist’ approach, and it’s great to see a brewery in the heart of New York City trying things free from the pressures of shifting serious units of popular styles. Kensrue is enthusiastic, too, about the new wave in simplicity. He hails Maine’s Oxbow Brewing, and talks with a near biblical reverence for Hudson Valley’s Suarez Family Brewing.

Randolph Beer is a fun and energetic antidote to the chin-stroking seriousness of many craft beer bars.

It is a metropolis in permanent flux, but New York’s capacity to inspire never falters.

We self-pour Randolph’s own Iota Draconis, a funk fermented ale using Whistler’s personal mixed-culture barrel, and Beta Blend, a sour golden beer aged in French wine casks for six months on apricots, sumac and sumac berries, both are as complex as they are drinkable, and offer a glimpse into the mind of a brewer free to experiment as one should.

Drinking in New York is not as mysterious as it once was. The latent danger of dive bars has been replaced by mixologists in bow ties. The beer is better. The music is worse. The East River edge of Brooklyn is unrecognisable to anyone who saw it pre-2010s. But its spirit remains. There are still few places on Earth as exciting.