Hugo Freijanes and Zak Elfman meet in a bar in Vigo, a city in Galicia on Spain’s northwestern coast. It’s a ‘blind date’, set up by their girlfriends who work together in the fashion industry. The latter duo had discovered that the former duo have a shared interest in talking ‘fermentation’, and thus a friendship was born.

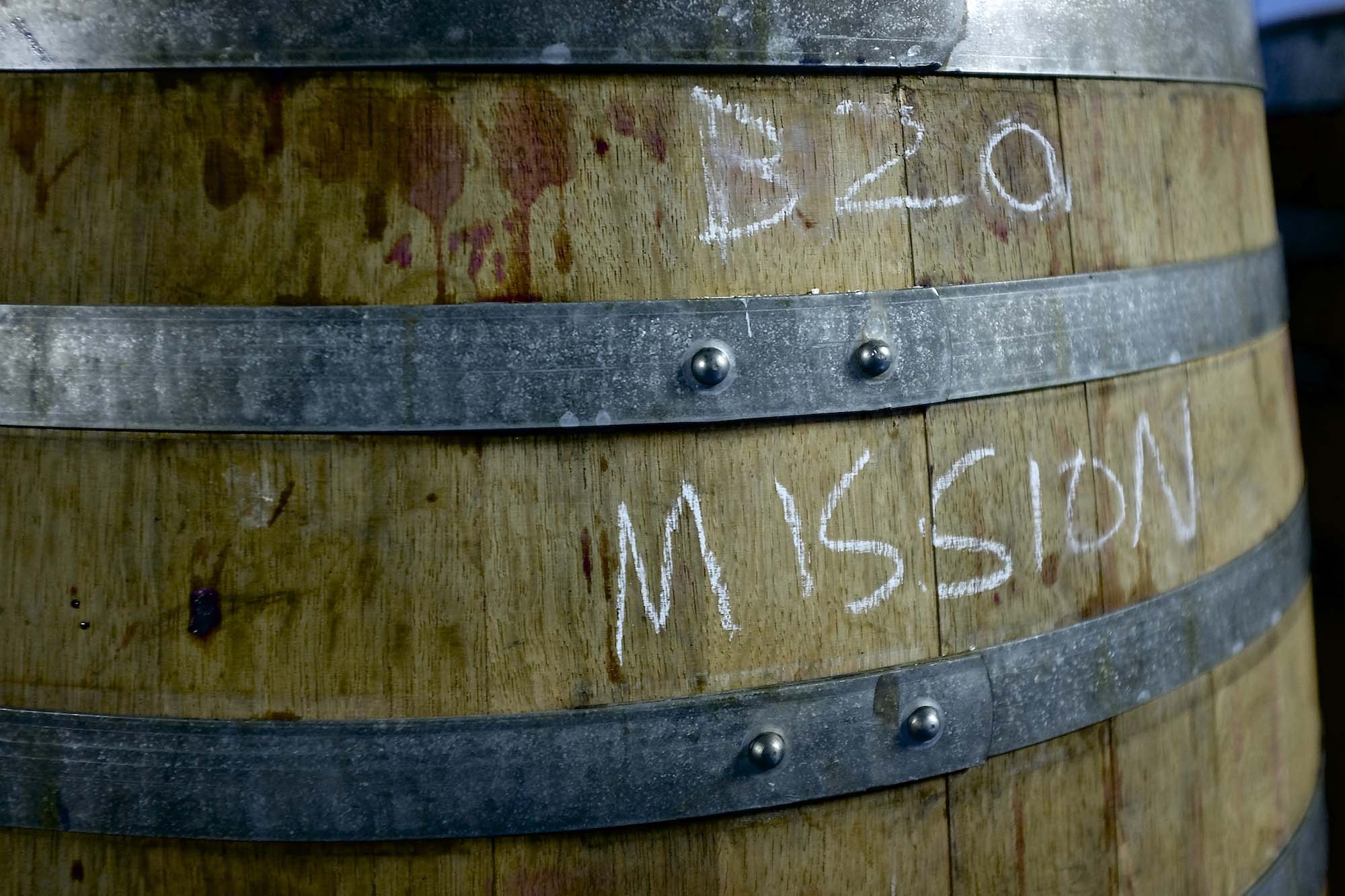

Zak is a North American making small-batch natural wine in the obscenely beautiful Ribeira Sacra; a region with winemaking tradition that goes back to the Romans, yet one that has not been overly exploited. Under the name Mission, Elfman is committed to a minimal intervention approach, creating a harmony between balanced and approachable yet complex and compelling. Hugo is the beer-nerd brewer behind Misterio Brewing, a fledgling beer brand based in Viveiro, a small town on the coast of Lugo. Other than a keen interest in bacteria, the two share a passion for producing honest, fuss-free beverages with a devout focus on drinkability.

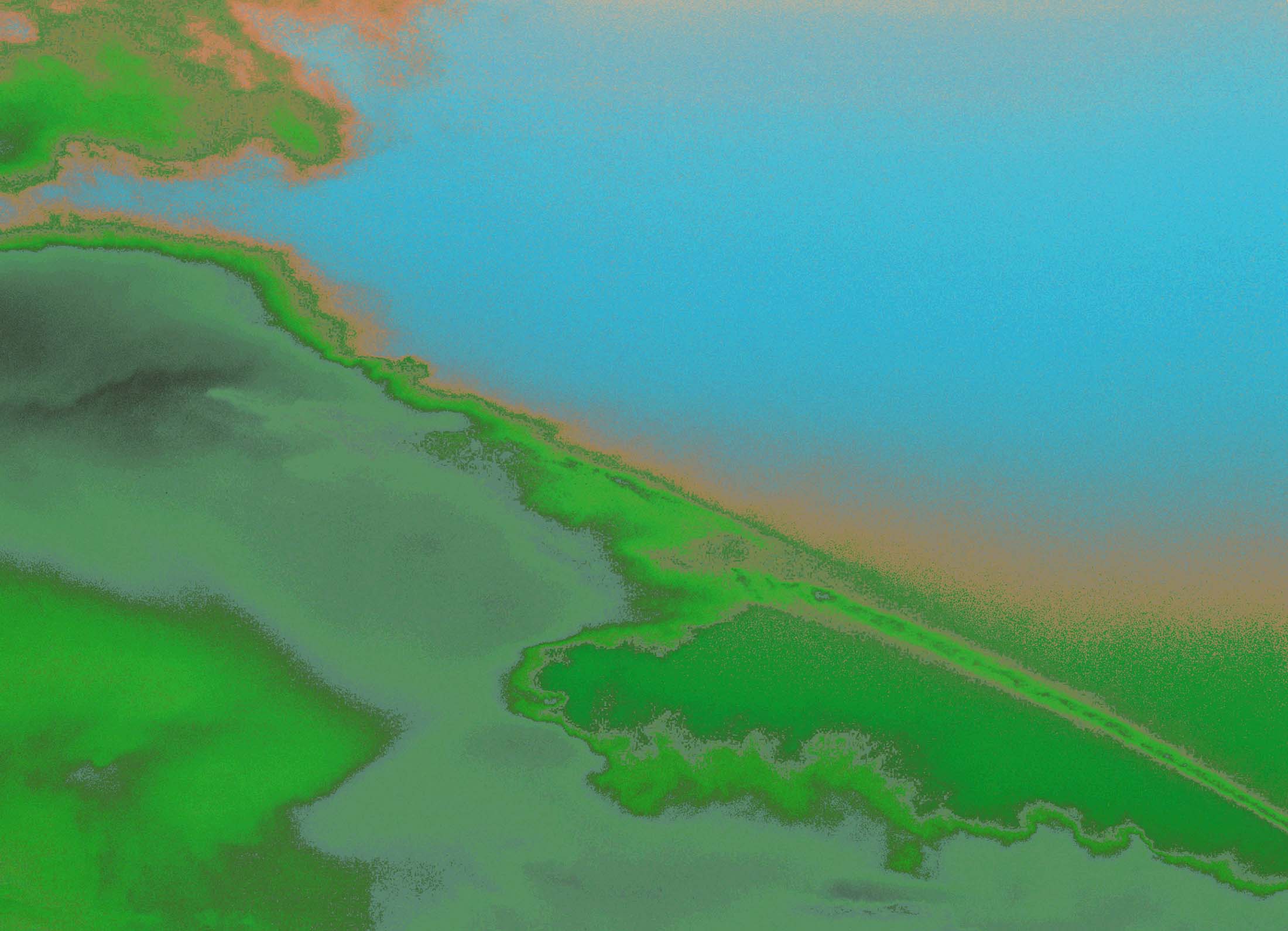

Zak Elfman in the Ribeira Sacra.

Hugo Freijanes.

The San Francisco Bay Area native has been tending to vines in northern Spain since 2015, having arrived on the back of stints in Mendoza, Argentina, and Stellenbosch, South Africa. Freijanes is two years into a project that he founded after ditching life in Barcelona and a career in graphic design to move to Utrecht, Netherlands, and embark on an education in brewing at Brewpub De Kromme Haring. Here, the Viveiro-born creative would serve as assistant to former biologist Stephen Grigg; the two experimenting in a myriad of beer styles with near-obsessive focus upon fermentation and obscure yeasts. Little has changed, Misterio is a brewery connected to simplicity; a yeast-forward operation with German-level attention to detail.

Different backgrounds, different worlds; a single shared vision. Elfman’s practice is one intrinsically rooted in the concept of ‘terroir’; Freijanes is a brewer eager to bring that essence into the world of craft beer. A shared vision of nature, provenance and place.

Naturally, the conversation turned toward collaboration, and Freijanes would head out to assist in harvest and bottling; assimilating the craft of winemaking along the way. Returning the favour, Elfman is assisting in Misterio’s forthcoming wood-ageing project; Hugo having made his own wine for blending with beer. Much is made of the crossover potential of natural wine and craft beer, here in Galicia one friendship is already bearing fascinating fruits.

To learn more about a friendship-turned-collaboration that is imbibed with the essence of wine and beer culture, a coming together founded upon a fondness of fermentation and a dedication to the essence of terroir, we took it back to the beginning. A bar in Vigo. A musing on beer history and beer future, a winemaker surrounded by terroir and a brewer searching for craft beer’s own … it’s time to hand over to Hugo and Zak.

The Ribeira Sacra. Photo, Andrew Whiting.

Misterio and Mission.

Hugo Freijanes: Something that interests me in particular, and something I think about frequently, is the concept of ‘terroir’ in beer. From my understanding, for you winemakers, this is a very natural idea that has been——more or less——respected and tied to quality for the whole history of your craft. Before getting deeper into the topic, I’d like to know your view on beer and terroir …

Zak Elfman: Maybe the reason I’m such a firm believer in the idea of terroir, and prefer terroir-driven wines, is because I’ve been in Europe for so long. But many, maybe even the majority of my American winemaking counterparts do not even believe it exists, and cast it aside as a French marketing tactic after Napa Valley wines beat Bordeaux in blind tastings during the 1970s

But I digress … In relation to beer, what comes to mind are locally developed styles such as New England IPA, that has become a bit of a thing. It is set within a region where the style was popularised, but now there’s NEIPAs being made all over. Obviously this is not terroir in the sense of winemaking, where the grapes grow in this place and they are influenced by the soil and the weather and the people around it. So, can we have terroir in beer?

“My point of view is that what makes a beer different from one another is the practices of the brewer itself; how it’s made. Because, for me, it’s a more artificial process than wine.”

HF: New England IPA was named like that because indeed it was invented in that region, but like most beers being made nowadays, it was brewed with ingredients coming from all over the world. The yeast originally used, which was believed to be a key part in the recipe, came from the UK; as well as some of the malts, and hops that came from other parts of the US.

Sure, in a traditional sense, that was not terroir. Nowadays the source for ingredients is so global that it is more about individual breweries making an impact on a local market and shaping a new product in conjunction with consumer tastes. In the case of NEIPA, that style appeared there and not somewhere else for some reasons. My point of view, and I may have read this somewhere, is that what makes a beer different from one another is the practices of the brewer itself; how it’s made. Because, for me, it’s a more artificial process than wine.

Hugo inspecting local hops in Galicia.

ZE: Not artificial, but it requires more human intervention. With this sense of terroir I am picturing Germany in the 16th century, or Britain or Belgium, and people are making beer. It’s all spontaneous fermentation in vessels made out of wood; there was no commercial yeast back then. Brewers used whatever barley and hops they could find, which was probably within a pretty tight geographical radius.

HF: Back then the fermentation was not 100% spontaneous. They harvested the slurry from the bottom of the fermenters and they put that into the next beer. I’m not sure if they knew what yeast was, but they knew that it was important.

ZE: Definitely, and I think for winemaking as well. But there was no commercial yeast that was being flown in from all over the world, and so that slurry tended to stay in one place. Maybe it was transferred among the Belgian monks or what have you, but I think that it probably stayed more or less local and so there was ‘terroir’ back then. There was a certain yeast that was used to ferment, there were local hops and barley and malt, so I think if you go back there was a sense of terroir. Beer would have tasted very, very different if you went from one village to the next; or from Munich to Britain. So what happened, why are we left without that?

HF: That’s the modern world.

Misterio Brewing.

Mission Wine.

ZE: Ha, yeah. So that has happened with wine as well, and now some of us are moving forward by going back. So we are trying to rediscover that ‘terroir’ and, of course, it’s easier with wine because vines are stuck in the ground and harder to transport around the world in the form compared to hops, malt or yeast. Do you think terroir can be rediscovered in beer?

HF: I would love to think that. I think it can be ‘artificially discovered’. I don’t know if that makes sense, but we have to work for it to be possible. Especially in this part of Spain where there’s no brewing tradition. If you come here and you want to make wine you already have grapes that are local that you can use. It’s easy. You just pick them, ferment them, and because the grapes grew here and they are a particular variety, you’re going to have ‘terroir’.

“If you spontaneously fermented wort in any part of the world, it’s very unlikely that something delicious and at the same time completely different from lambic is going to appear.”

But if you want to make beer in Galicia, there’s only so many local grains that you can use. In Misterio we’ve already experimented with local raw wheat in one of our recipes. Malted grains are trickier because there are no malters in the region, and the closest ones are not paying attention to what craft breweries ask for yet. Besides, I don’t know how much barley is being grown here, or if there is a local barley variety. There are some hops, mostly German varieties grown here, but not for too long. And then there’s the microflora, the ingredient that has been here for the longest time.

But if you go for 100% spontaneous fermentation with the microbes in the air, after ageing and blending the end result that you are going to aim for is going to be influenced by Belgian tradition; you’d be basically making lambic. And that’s what is happening in the US.

Hugo isolating bioprospected local yeast;

a work in progress.

ZE: Not a bad thing to aim for, lambic is delicious.

HF: Of course it is. What I mean is that if you spontaneously fermented wort in any part of the world, it’s very unlikely that something delicious and at the same time completely different from lambic is going to appear.

ZE: Having an, I guess, authentic ‘beer de terroir’ is going to be difficult. It’s not going to be delicious, and it’s probably going to take a long time to get the refinement of that and to understand how it ferments. That’s at odds with the easygoing drinkable beer made with yeasts in the conventional styles that we’re used to.

HF: Some part of the traditional styles came from what ingredients were available back then in the area, but there was also room for creating different recipes and using different processes. Those decisions were based on what the public demanded, and I’m sure the public’s palate has changed over time; like we are seeing now in the craft beer scene, but in a more localised manner.

This second craft beer revolution is so global that those local trends and tastes either don’t have the opportunity to appear at all or, if they do and become successful enough, they get replicated all over the planet so quickly that they lose their geographical connection. On top of that, the majority of beer consumed worldwide is made by big commercial breweries, and doesn’t drift too far from bland light lager.

Hollow Tree, a sessionable, malty and dry amber saison; an exploration into the subtle richness of German malts and ‘pseudo-noble’ hops, Loral and Hallertau Blanc.

ZE: Exactly. Without getting too political, it’s like McDonalds is the lowest common denominator of food in the world, so we have McDonalds all over the world … and, for the same reason, we have crappy lager all over the world.

HF: Except that McDonalds is not so omnipresent in some European countries like Spain and Italy; because we have such a great variety of local traditional foods.

ZE: So, do you see much cheap lager being drank in Belgium, because they have so many local traditional beers?

HF: From what I know, people in Belgium are proud of their beer diversity and like to drink specialty beers from time to time, but commercial lager is also strongly present there; and Belgians have a strong connection with their regional brands. That’s something that happens everywhere, like here in Spain, people from the north would tell you that the beer from the south is disgusting and vice versa. Those beers are not necessarily better than each other, people just relate to them because they became part of their regional identity. I think this happens in every country, and it’s probably a reminiscence of what this ‘beer terroir’ used to be.

Misterio Brewing.

ZE: Beer must have been brewed here hundreds of years ago, right?

HF: If it ever was, it was lost at some point, that’s for sure. Probably the Romans …

ZE: No, probably more recently. Maybe during the industrial revolution there were more local brewers around Spain making local beer. I’m sure the ones we have now grew faster and simply outcompeted the rest.

HF: Again, I’m not an expert in beer history, but when you start digging into the origins of those big companies (outside countries with tradition in beer) you always read about the story of some businessman who travelled to Germany to learn about the craft. That tells you that there was likely nothing traditional here beer-wise to build upon.

ZE: So with Misterio, you are obviously not trying to make bulk lager. What qualities do you want in your beer?

HF: I think drinkability is the first thing that comes to my mind. For me that means something that does not clash with you in any way. Most of the time I don’t want to think about what I’m drinking too much. I don’t want the beer to interrupt other things that I’m doing. And when I focus on it, I want it to be nice, without off-flavours or faults, because that’s also a distraction to me.

“I don’t want my wines to overwhelm anything you’re doing, or any food you are eating, but then if you focus on them, I want them to be interesting.”

ZE: I want my wines to be the same way. I don’t want them to overwhelm anything you’re doing, or any food you are eating, but then if you focus on them, I want them to be interesting; so you can ignore everything that’s going on around and get enjoyment just from the glass. Be drinkable, but also have something to say.

HF: I think that those qualities would make it approachable to all kinds of people.

ZE: If that’s the profile you are going for, what would you do to make your beers like that?

HF: I often think about my mum drinking it and think if she would like it. It’s not that I’m aiming for my beers to be marketable to everyone, but this happens to coincide with what I want from beer: drinkability and freshness. I would avoid malts that are too strong in flavour unless those are called for by the style I want to brew. Also, what I like about the yeasts that I work with, is that most of them are highly attenuative, and they produce drier beers that are more refreshing; which contributes to my aim of drinkability.

ZE: Interesting, because usually, in the wine world, a little bit of residual sugar, people like that. And people find it more drinkable. If a wine is too dry, people will find it off-putting, and from my part I make all my wines dry. Not that it’s better or worse.

HF: Maybe in wine you have acidity playing a bigger role.

A wine Hugo is fermenting for future beer blends.

ZE: Acidity does play a big role, but acidity and sugar are two things that you want to balance in some wines. The tension, which is a very often used term for rieslings, is a balance between high residual sugar and high acid. Wine has much higher acid than beer, and so because of that, it is also capable of having higher residual sugar … I think. If you have a lot of acid and you have very low residual sugar, the wine can seem very harsh to most people out there. So that’s something that you have to keep in mind.

I was thinking about the ‘ageability’ of beers; styles that, with time, become something special. I’m curious, because I don’t know what the answer is for what makes a wine ageable or age-worthy, and maybe the secret lies in something that you know about beer.

HF: Usually a more alcoholic beer ages better than a lighter one. Microbiological complexity helps in the long term as well. Before the advent of sanitation in the brewery, that complexity was not always intentional, but it helped anyways. Belgium farmhouse ales used to be brewed in the end of the summer and stored during the winter to age. I think people liked the way in which the flavour evolved, and in Galicia we have that, we have a cool winter that could be used for that.

ZE: I completely agree for wine. And I think one of the factors that makes a wine ageable is microflora that’s still alive, that has not been killed off in the winery and can continue surviving in the bottle; though at a low activity level. How do we try to cultivate those slow-working microflora in the brewery or the winery? What are some things we can do?

HF: I don’t think you necessarily cultivate those, they are everywhere.

ZE: You just have to allow them to be.

Harvesting on the Ribeira Sacra.

Hugo Freijanes Senior helping with Misterio’s foray into winemaking.

HF: Yes, from what I’ve read saccharomyces, bacteria and brettanomyces work together, and they behave differently when some are present and some are not, so it’s very difficult to predict their outcome; especially when you are experimenting with new recipes. That’s why blending is a key part of long-aged mixed fermentation beers. Because you don’t know how one barrel is going to end up, so you may need to put some balance in that.

ZE: Blending is difficult for me right now as well.

HF: When you blend a wine, does it change a lot afterwards?

“I think a lot of people have been brought up on certain wine styles, and they get used to the supermarket wine style. And if they’re used to that, they think it’s good, and it’s hard for them to jump into more artisanal wine styles.”

ZE: Tremendously. There are some regions that are famous for blending and some regions that are famous for making single vineyard or specific grape varietal wines, and many different skill sets are required in the winery in the blending regions compared to the others. Galician wine is traditionally from single vineyards: the famous minifundios. But I have met some very talented people who were able to blend, and who really like those wines as well, especially when it comes to drinkability.

HF: How do you see wine in Galicia evolving?

ZE: Good question, I think that the raw potential is so great and so attractive that it’s going to be a continued attraction to this place and investment in the space; and it’s going to be exploited to a certain degree by some. You already see some wineries and wine companies coming in to certain parts of Galicia with investments just to capitalise on what is naturally here, and I thinks there’s gonna be, hopefully, a continued interest from winemakers that want to come here and make something special.

And I think that’s going to be the two paths that the future of winemaking in Galicia takes. Of course there is the existing interests which want to sell supermarket wine, but that’s always been here and always will be. That’s an unfortunate reality of the space.

Photo, Andrew Whiting.

HF: Do you think that supermarket wine is easier for the consumer than what more interesting winemakers are doing here? Or is it just a matter of economy, in that it’s much cheaper?

ZE: I think a lot of people now, it depends on the age group, but I think a lot of people have been brought up on certain wine styles, and they get used to the supermarket wine style. And if they’re used to that, they think it’s good, and it’s hard for them to jump into more artisanal wine styles, or more real wine.

Wine enjoyment is something that is very subjective as we’ve been talking, so when somebody believes something is good and they go to the supermarket or the wine shop, they see something with a lot of points from critics and they bring it home, a lot of people don’t have the confidence to say if they like it or not, so they believe the critics and the points and the guy at the wine shop.

Once you start your own brewery, if you want to maintain that mentality, you must have a really strong vision of what you want to pursue, or you’ll get caught up in the latest trends. Breweries like that are rare, and as likely to appear here in Galicia as anywhere else.

So they develop their palate thinking: “oh, this is good wine.” But actually it’s not. It’s garbage, it has been bought in bulk, it’s been treated by an enologist with a vast array of chemicals and products that are thrown in there, but the consumer thinks it’s good. Then one day when they’re confronted with real wine it’s a shock to them, and they don’t know what to do with it. Even if it’s perfectly clean, non-defective, real wine, it’s still something different from what they’re used to, and different from what their conception is of ‘good wine’; and so it’s casted away. Thus it will always be a niche product in this modernised grand world of industrialisation. Sorry, that was a lot.

HF: No, that was perfect. I see beer reflected there in many ways. First in the training of consumer palates, and the defining of expectations from the commercial beers. You can have a clean, super well-executed porter, for example, and people don’t like it because it’s something different and something new.

Trapdoor is a saison with Galician Callobre wheat; a local variety almost extinct until very recently.

ZE: Right. So, here in Galicia, I want to ask you: what do you see of the future market in the consumer side and the producer side? Do you have faith in the consumer that has been brought up on commercial lager, that they’re able to adapt to real beers being made? Or do you think that it’s still going to be a small niche product on the fringes, that real, well-made beer will continue to be only available in specialty shops, only in one or two bars in a city, not to be found in the countryside? Or is it a brighter future, is it going to be more widely adopted?

HF: I think it’s going to be more present for sure. It’s easy to see in this part of Spain how things are following the trends in bigger cities. In Madrid and Barcelona we’ve seen in the last years craft beer appearing everywhere, like in small corner shops, and in restaurants that are not dedicated to beer. That is starting to happen here, but not so much yet. Eventually I think it will, there’s nothing really too different from the rest of the country in Galicia. But if you want to talk about something really unique happening here regarding beer styles, there’s a lot of work to be done. And that’s exciting.

ZE: So confidence on the demand side, but no so much on the supply side?

HF: Well, there’s people pushing the boundaries of beer everywhere nowadays. Just take a look at the online homebrewing communities; there’s so much information there, and everybody is experimenting and learning from one another. It’s great. On the other hand, once you start your own brewery, if you want to maintain that mentality, you must have a really strong vision of what you want to pursue, or you’ll get caught up in the latest trends. Breweries like that are rare, and as likely to appear here than anywhere else.

The End.

Indeed, breweries like that are rare, yet becoming less so. Misterio is one, and their forthcoming wood-aged beers——with minimal intervention from one Zak Elfman——are ones to watch. Craft beer has much to learn from winemaking, and the brewers open to that are the ones whose offerings should be most eagerly anticipated.

Terroir is more than a concept, in a world where reconnection to nature is more critical than ever, provenance and place is the one way forward that matters. At times it can feel as though there needs to be a greater gulf between craft and industrial beer, conversations like this are the beginning.