The barrel room at Purpose Brewing & Cellars in Fort Collins, Colorado, is compact, yet every inch within it is made available for the storage of steadily maturing beer. It’s the first thing to catch your attention when you enter the brewery’s taproom. Once you do, it’s difficult to turn your attention away from the collection of various oak casks, as you sit and enjoy a flight of beers within comfortable surrounds.

It’s a certainty that many of these barrels have a storied history, most having contained wine or whiskey for many years beforehand. However, one of these barrels——which appears maybe a little more haggard than the rest——has perhaps the most significant story of any barrel used in the beer industry to date. In fact, it may well be responsible for the American sour beer movement as we know it.

It’s name is pH1, and it’s easily identifiable, as this marking was permanently inked with a marker pen front and centre more than two decades ago.

pH1, ‘The Rare Barrel’, at Purpose Brewing & Cellars, Fort Collins.

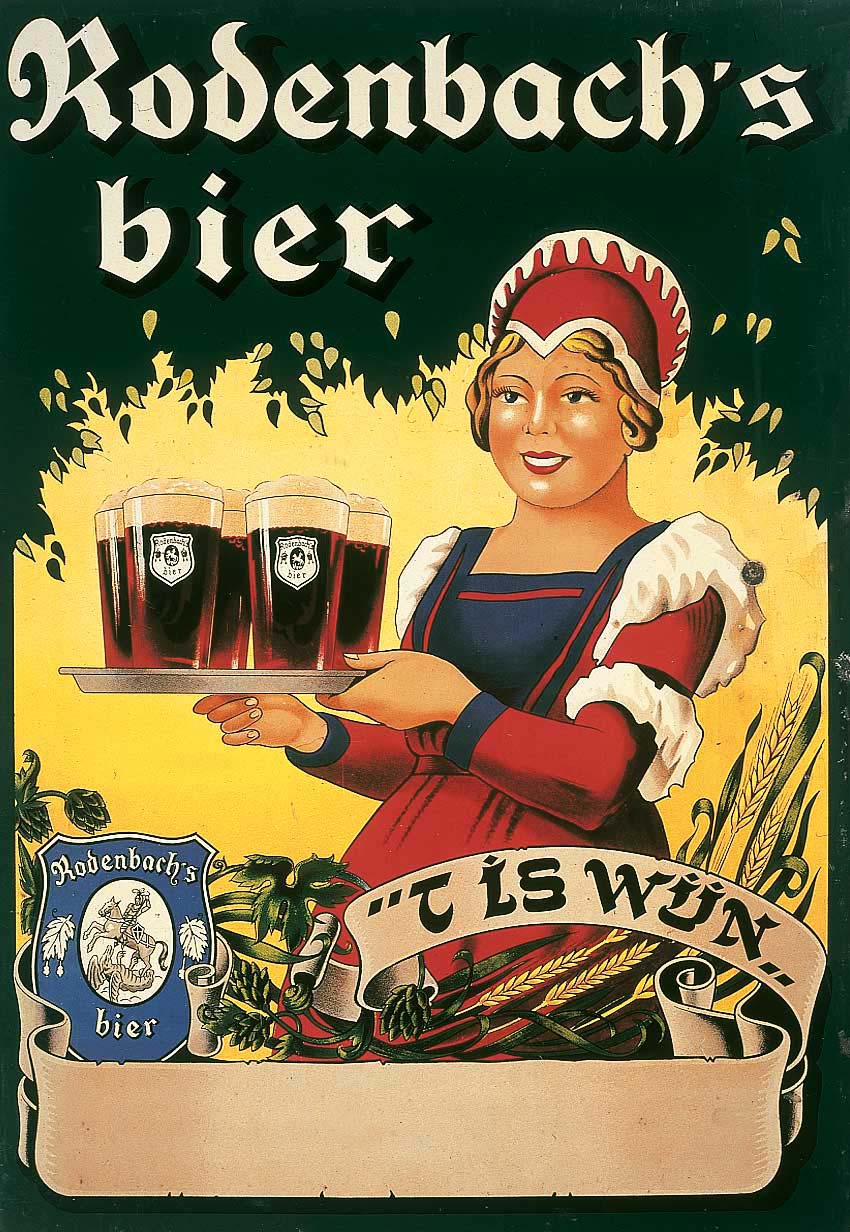

pH1, which also goes by the nickname ‘The Rare Barrel’, was one of a number of specially acidified or ‘pre-soured’ barrels acquired by Colorado’s New Belgium brewing in 1997. Brewers Peter Bouckaert and Lauren Limbach used this, along with a handful of other barrels, to mature the brewery’s early batches of sour beers. Bouckaert already had considerable pedigree when establishing the program, having formerly worked at Belgium’s famous Rodenbach brewery, one of the world’s most highly regarded producers of sour beer.

New Belgium’s sour program, which exists at the brewery’s Fort Collins facility, has since grown to become the largest of its kind in the US. The wood cellar at New Belgium is now home to 64 giant oak vats known as ‘foeders,’ while some of its sour beers, such as the tart and bittersweet La Folie, have become nationally recognised brands.

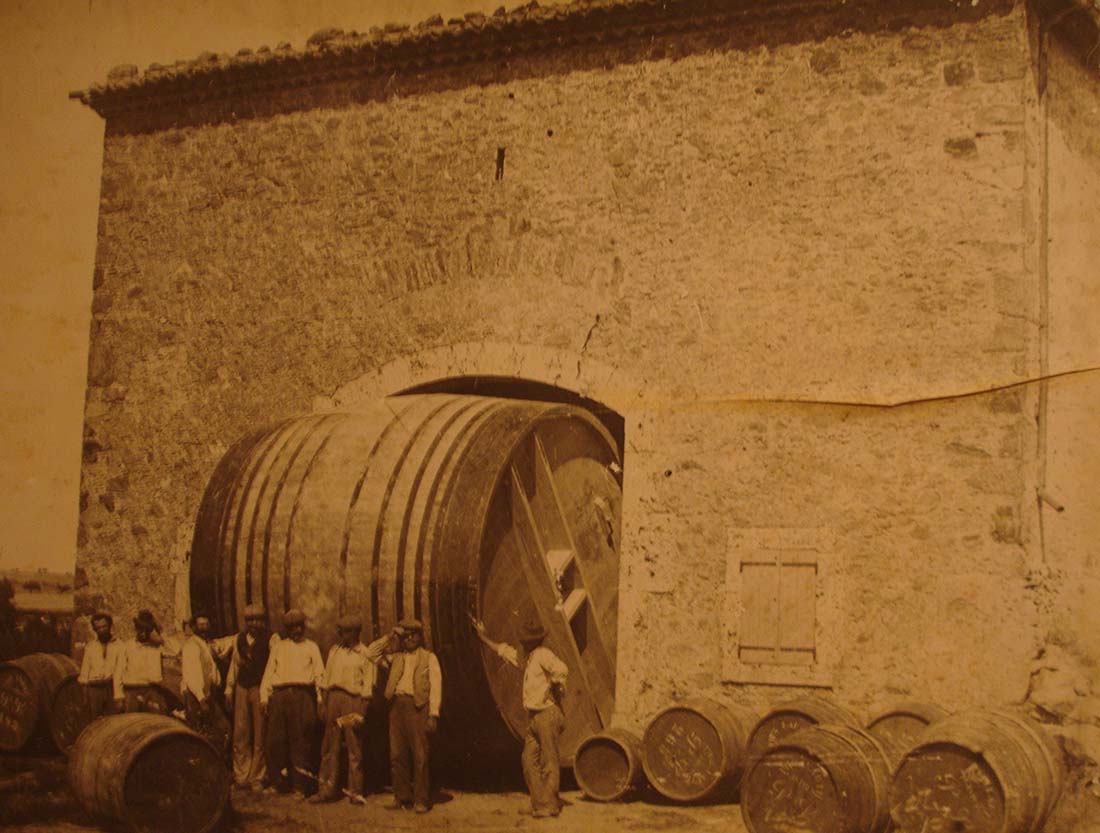

Photograph of an early foeder, from an exhibition at L’Abbaye de Caunes-Minervois, Occitanie.

La Folie © New Belgium

The Rare Barrel’s story didn’t end there either. Bouckaert eventually decided to gift the barrel to his friend Vinnie Cilurzo at California’s Russian River; a brewery perhaps best known for its perennially adored double IPA, Pliny the Elder. Like Bouckaert and Limbach before him, Cilurzo used pH1 to launch his own sour project, one heavily inspired by the wine production that takes place in the Sonoma Valley, where his brewery is based.

Eventually, the barrel would move on again, this time falling into the possession of a young brewer called Jay Goodwin, who would even name his brewery——The Rare Barrel——after the vessel that inspired its inception. And so it came to pass that two years after founding his own brewery, Goodwin learned that Bouckaert was ending his two-decade career at New Belgium to start a new project, Purpose Brewing and Cellars. This was all the impetus he needed to return the barrel to its former owner, which is how pH1 came to be back in Fort Collins.

“I’m not sure where it’ll go when we’re done with it,” Bouckaert tells me. “But it doesn’t feel like its journey is finished just yet.”

Purpose Brewing & Cellars

The American Dream.

Over the development of the modern beer era, sour beer has well and truly captivated the palate of the American drinker. Imported beers from Belgium, such as those from Brussels’ famous Cantillon brewery, has likely had as much of an impact as the arrival of talent such as Bouckaert himself. A decade ago barely anyone had heard of Cantillon, or other producers of the indigenous Belgian sour beer known as lambic, such as Brouwerij Boon or 3 Fonteinen.

Fast forward to the present day and you can barely buy Cantillon in the US for love, nor money. Entire slabs of hard-to-get beer are traded for rarer bottles and increasingly large sums of cash. It was beers such as those produced by Cantillon, which captivated another young Colorado brewer, Troy Casey; founder of Casey Brewing & Blending in the mountain town of Glenwood Springs.

“We don’t make any other styles besides sours,” Casey says. “We probably lose some business because we don’t brew an IPA or a stout, but this just makes us work harder at making the best sour beers we can, so that we can attract more customers.”

Photographs © Casey Brewing & Blending.

Casey spent much of his formative years brewing for Coors at its AC Golden facility not far outside of Denver. He studied under Professor Charles Bamforth at UC Davis in California; considered by many to be one of the foremost schools of brewing science.

The Cut: Grape

© Casey Brewing & Blending

You might not expect a brewer of this pedigree to end up leaving that world behind to focus solely on the art of sour beer. However, it was behind the scenes at AC Golden where Casey first started experimenting with the various strains of yeast and bacteria that would eventually serve as the foundation of his own brewery.

To the aficionado, Casey’s beers might not even come across as sour. Such is the refinement of beers such as The Low End, a delicately tart saison, or the intensity of fruit in a series known as The Cut. You might even be forgiven for mistaking these beers as being Belgian in origin, such is their pedigree. Newcomers to the style will perhaps find their sourness challenging, but there’s a delicateness to Casey’s products that also makes them beguilingly accessible.

“It’s always fun going to a beer festival and watching someone try their first sour beer,” Casey continues. “We’re then able to explain the process and most people like them, I think.”

He also remarks that it wasn’t too great a challenge establishing an all-sour brewery in Colorado. The mountain state is one of the most prolific when it comes to craft breweries after all, and of course when it comes to American sour beer, it has history.

“The biggest change for us over the last 20 years has been our fundamental understanding of the souring process.” The limber figure of New Belgium’s Lauren Limbach leaps through the so-called ‘foeder forest’ at New Belgium, collecting a sample from one of the oak vessels. Limbach serves as the brewery’s master blender, remarkably keeping notes on all of her maturing beers entirely by hand.

“I can taste a barrel and tell you exactly where a beer is and what’s currently happening to it,” she says. “The biggest thing for me has been letting the science creep into that process, it’s fundamental to everything we do.”

“It’s always fun going to a beer festival and watching someone try their first sour beer. We’re then able to explain the process and most people like them, I think.”

Limbach equates the rise in popularity of sour beers to that of the farm-to-table movement that food culture has experienced; despite admitting the comparison is a little cliché. However her point is a salient one, as the increasing interest in how things are made and where they come from has significantly benefitted sour beer.

Beer people talk about yeast strains such as Brettanomyces and bacteria such as Lactobacillus in everyday conversation. The detail that goes into the fermentation and maturation of sour beers gives it a strong sense of place, or terroir, much like in wine. It’s a clinging point that has anchored enough interest to give the category the momentum it needs to be catapulted successfully into the mainstream.

© Rodenbach/Palm Breweries

Brouwerij Boon © Dirk Van Esbroeck

Belgian Vinegar.

Without the influence of the Belgian brewers, there might not be any sour beer left in the world at all. Or at the very least, the sour beer landscape would look a great deal different to what we know now. Even the currently popular sour red and brown ales of West Flanders, or the lambic and gueuze of the Pajottenland to the southwest of Brussels, were not immune to the shifting of the Belgian palate that occurred post World War II.

The introduction of heavily sweetened beverages such as Coca-Cola around the end of the Second World War are held somewhat to blame for the closure of hundreds of small breweries across Belgium in the decades that followed. Tastes shifted away from the sharp, lemon zest sour and bone dry lambic; a beer that was considered a “drink of the people,” as once put to me by Frank Boon of the eponymously named Belgian brewery.

Lambic, and its blended, bottle-refermented sister, gueuze, seemed as though it may have reached the end of its days.

Rodenbach.

Belgians, however, are resolutely stoic in the face of their traditions being eroded. Frank Boon was one of a handful of lambic producers instrumental in the preservation of this tradition, and he did so in part via the formation of HORAL, The High Council for the Preservation of Artisanal Lambic Beers. The existence of HORAL, however, is only part of the story, with the passion of individuals like Boon, and others such as Armand Debelder at 3 Fonteinen playing more of a role in its revival that in their modesty they’d care to admit.

“Belgian’s in the ’90s had this idea that lambic was just vinegar,” Frank Boon told me on a visit to his brewery in Lembeek, to the south of Brussels, a couple of years ago. “[We] decided that people needed to be educated on what makes a good glass of gueuze. HORAL is a part of why gueuze is becoming so important.”

Lambic is created via a process known as spontaneous fermentation. Here, the wort created in the brewing process is inoculated and fermented only by wild yeasts. To achieve this, this wort is pumped into a large, flat metal container known as a coolship. As the beer cools overnight the wild yeasts looking for an easy meal are drawn to it. Once inoculated, the beer is transferred for fermentation and maturation in oak casks the following morning. It’s the yeast and bacterial equivalent of a one night stand.

3 Fonteinen.

Over a number of months and years the flavour of the lambic will develop thanks to the mixture of yeasts and bacteria present in the barrel. Remarkably, it’s still considered to be young beer up to 18 months in age, and tasting it at this point will reveal soft, sweet flavours, with a prick of lemony acidity. Old lambic can be aged for three years, or sometimes even longer. It’s considerably dryer in the finish, with an incredibly sharp acidity. However, it’s when young and old lambics are blended and bottled to become gueuze, that the art form reaches its apex.

The importance of gueuze and its influence on the culture of sour beer production around the world cannot be understated. As well as inspiring sour beer producers all over the world, it’s even inspiring new producers on home turf. Pierre Tilquin has been producing his own gueuze since 2009.

However unlike producers such as Boon, Tilquin does not produce his own wort, instead sourcing it from other producers. It’s then fermented, matured and blended in order to produce the finished product. This type of traditional blendery, or geuzestekerij to use the Flemish dialect, was common in Belgium before lambic fell on hard times after the war. Somewhat fittingly, until very recently it was the same method used to produce beer by Troy Casey, some 5,000 miles away from Belgium, in the heart of the Rocky Mountains.

Burning Sky

The Wild Beer Co

Cool Britannia.

The UK is something of a sponge when it comes to beer trends that develop overseas. It will openly adapt other brewing cultures in order to expand its horizons. The global sour beer movement has been gradually encroaching upon British brewing culture. What’s most exciting about this for me is that Britain’s brewers having a habit of making these absorbed cultures their own, making it an incredibly exciting time for sour beer lovers in the UK.

‘The Coolship’.

2017 saw a significant happening in the UK, with Burning Sky brewery installing the first newly commissioned coolship that Britain had supposedly seen since the 1930s. In the UK, coolships were traditionally used merely to cool wort (and a thorough beer historian will often remind you that we called them coolers instead of coolships) rather than inoculate them for the production of beers similar to lambic.

Burning Sky’s intention, however, is wholly dedicated towards paying homage to these Belgian brewing traditions. It should come as no surprise that several other breweries in the UK also intend to, or have already began producing spontaneously fermented beers; with the country’s largest independent brewer, BrewDog, already having its own coolship beers in maturation.

Spontaneously inoculating wort is just one chapter in the story of wild fermentation, however. The bulk of the story lies within the barrels themselves. In deepest Somerset, just a stones throw from the Glastonbury Festival site, The Wild Beer Co has built up what might be the largest collection of maturing sour beer encased in oak within the UK (BrewDog’s Overworks project notwithstanding). US expat Brett Ellis founded The Wild Beer Co along with business partner Andrew Cooper in 2013.

The Wild Beer Co.

“Andrew and I have never wanted to bring sour beer to ‘the mob’ but equally, we didn’t want to only have a few oak barrels in a nano-brewery either,” he says. “Our aim is to introduce as many people to world class and authentic wild beer as possible. Living out that ambition could possibly create ubiquity, which could be either a hindrance or an advantage. The key, as I see it, is authenticity and quality.”

With their array of sours, saisons and farmhouse-inspired beers, the likes of The Wild Beer Co and Burning Sky may once have been perceived as a blip on the UK beer radar. I feel it’s important to note there’s not a great deal of money to be made from producing sour beer. It takes a long time to make, and if a beer is sitting in oak for three years, well, it’s not paying for the roof over your brewery while it’s in residence. To make up for this shortfall, both of these breweries produce pale ales and other styles with quick turnarounds.

© Little Earth Project.

© Mills Brewery

Although, recently within the UK, a set of new, incredibly small-scale projects are emerging and succeeding in what you might expect to be a challenging market. Suffolk’s Little Earth Project is focussing almost solely on wild ferments and oak-ageing to glowing feedback. It could be that Britain too is seeing the type of palate shift that Belgium and the United States has seen in recent years.

“For us, the only way to produce the best wild and sour beers was to completely focus on just that,” Jonny Mills, co-founder of Gloucestershire’s Mills Brewery, tells me. “It allows you to enter a different mindset in terms of producing a beer. Every beer we release is a blend taken from several different brews, so our approach becomes much more about tasting and reverse-engineering. We work with the flavours in front of us to put together a great drink, as opposed to forward-engineering each brew and having to accept the product as it ends up.”

“For us, the only way to produce the best wild and sour beers was to completely focus on just that. It allows you to enter a different mindset in terms of producing a beer.”

Mills caused a stir with his first commercially available bottled beer, Foxbic. A blend of wild fermented and oak-matured sour beer with Foxwhelp apple juice provided by cider legend Tom Oliver, it effortlessly demonstrated the progress and maturity that British sour beer has made. Simultaneously expressing that there are still many more boundaries available to be crossed when the time comes.

What Belgium may have started, the US adopted with typical gusto. Now this has become one of the most exciting frontiers within brewing. The most thrilling part of the story being that only time, yeast and oak knows what exciting wild, sour and acid-forward beers we’ll be enjoying several years down the line.