Confident women have always been easy targets for ridicule. Women are used to having their credentials questioned, their appearance judged, and men given credit for their accomplishments. Even supposedly forward-thinking men are guilty of this deeply-ingrained casual sexism; recently so, Chris Funari, formerly of Brewbound.

The longtime editor of one of beer’s most influential publications was terminated from his position after he publicly ridiculed a number of beer influencers on a now-deleted segment of episode 44 of the Brewbound Podcast. Funari referred to a recent ‘best of’ list of beer influencers, making belittling comments about several accounts that he described as “chicks … in low-cut tops with beer,” going on to tell the women, “don’t make it so obvious.” (I’ll assume that when he says ‘it’, he means flaunting their bodies and sexuality publicly.)

Some rose to defend him, calling his termination over this incident “a waste” when considering his overall journalistic chops. Others, like Cat Wolinski for VinePair, supported the influencers Funari named, proclaiming: “all members of the beer community should be able to present themselves however they choose, so long as they’re not hurting anybody; it’s not up to us to dictate what’s best for anyone else.”

More and more conversations are covering the troublesome history that beer has with women.

I tend to be less than thrilled when men decide to police women’s bodies. But as a woman covering the craft beer scene, I also struggle with the residual impact that hypersexual content from beer influencers has on how the world may view me in the same space. With more and more conversations covering the troublesome history that beer has with women while acknowledging the potential damage this new genre of social media interaction can have on all women, I’ve come to realise one important truth: it’s complicated.

FEMEN, a female activist group seeking to ‘complete victory over patriarchy’, use their bodies to protest at the Palais-Royal, Paris

When I was first asked to write about the influencer phenomenon in craft beer, I said no. I didn’t know any of these so-called beer influencers, and I certainly didn’t follow any on social media. My initial thought was: why would I go out of my way to spotlight women actively perpetuating negative stereotypes of women in beer?

But my feminist spidey-sense tingled. Freedom of self-expression, including sexuality, can and should be celebrated as an empowering act for women who choose to engage in their own versions of it. Many women proudly consent to publicly pose nude in the name of feminist liberation; to conquer feelings of vulnerability; to promote body positivity; or to counter the slut-shaming pressures society places on all women.

If I support women reclaiming autonomy over the way they’re perceived by the world, even if it differs from the way I wish to be viewed, why wouldn’t my attitude extend to women beer influencers?

For context, I personally define ‘influencers’ as social media personalities working to cultivate relationships and possibly monetise said relationships in a specific industry. They are often women, often white, but sometimes neither. They tend to have thousands of followers and actively engage with them through very stylised, high-quality composed photographs posted on a regular (often daily) basis. And——this is important——they may or may not actually work in said industry.

I agreed to meet with two of the most recognisable beer influencers on Instagram: Megan of @isbeeracarb (26.2k followers) and Melis of @thegirlwithbeer, 77.2k followers), who both happen to live in the same town as me. They also both happen to be women. Over the course of our hour-long interview, I ran through my standard questions about their backgrounds, how they got into beer, what they like about it, and so on. Finally, I got to what I assumed would be the crux of the interview, basically: “do you think it’s okay to post sexually suggestive images to promote an industry that’s historically been problematic towards its depiction of and relationship with women?”

Megan, aka @isbeeracarb.

Melis, aka @thegirlwithbeer.

Their answers revealed my own misguided prejudices towards their endeavours. They’re open about the fact that their shared ambition is to leverage their accounts as professional tools to create relationships and grow in the beer industry. Both women already work in beer (Megan is a brewer, Melis works at a brewery doing marketing and PR), so they clearly have passion and expertise to justify their roles as influencers to those, like Funari, who would question it.

I’m no fan of sexist, racist, misogynistic, or otherwise harmful ploys for attention dressed up as a marketing plan. But to collectively decide that the professional contributions women make to the craft beer community can be dismissed because they decided to challenge the narrative their bodies are solely for male consumption is lazy at best. Hugely offensive at worst.

@isbeeracarb

Lily Waite, a UK-based beer writer, activist, and the founder of The Queer Brewing Project, has given exhaustive context to what’s sexy and what’s sexist in her essay The Male Gueuze — Cantillon, Cabaret, and Context for Good Beer Hunting. In the conversation about influencers’ roles and responsibilities in the industry, she weighs the benefits of women being able to choose how they’re portrayed against the reinforcement of the existing “sexist feedback loop” beer remains entrenched in.

Since its inception, beer has excused——if not actively perpetuated——inappropriate behaviour as part of a white male-dominated culture.

“I think that there’s nothing remotely sexist about a woman choosing to use her body however she wants: that choice is hers and hers alone to make, and as such, is inherently empowering … [but] it’s impossible to look at female representation and the use of female bodies in relation to beer without considering the historical prevalence of sexism, and the history of explicitly sexist marketing used to sell beer,” says Waite.

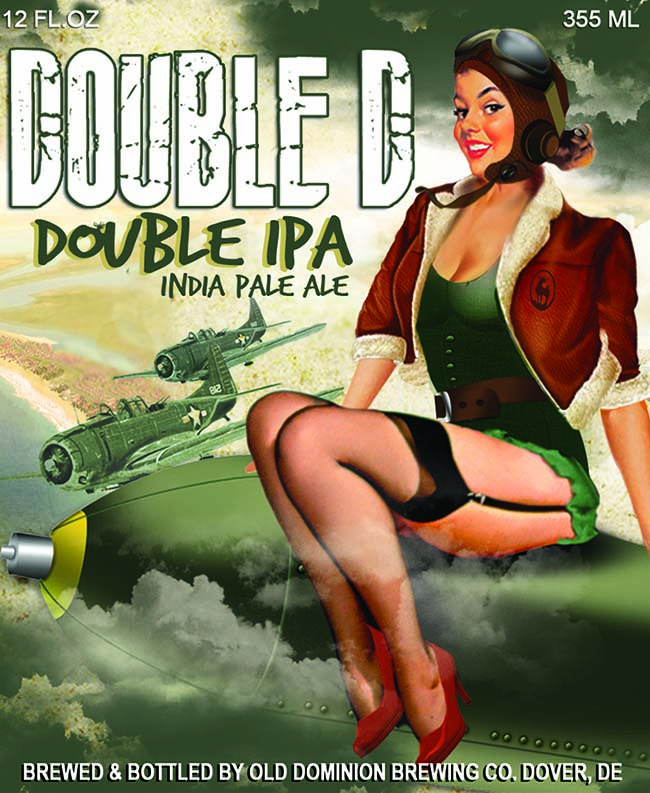

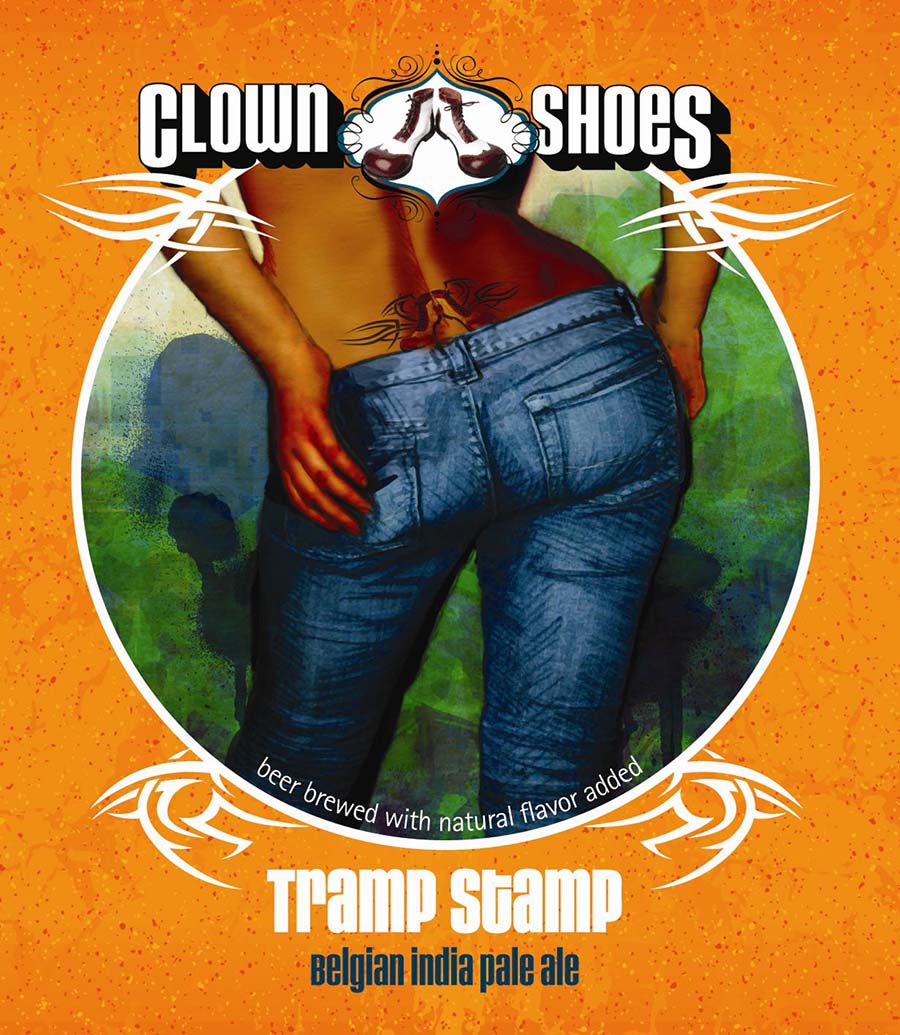

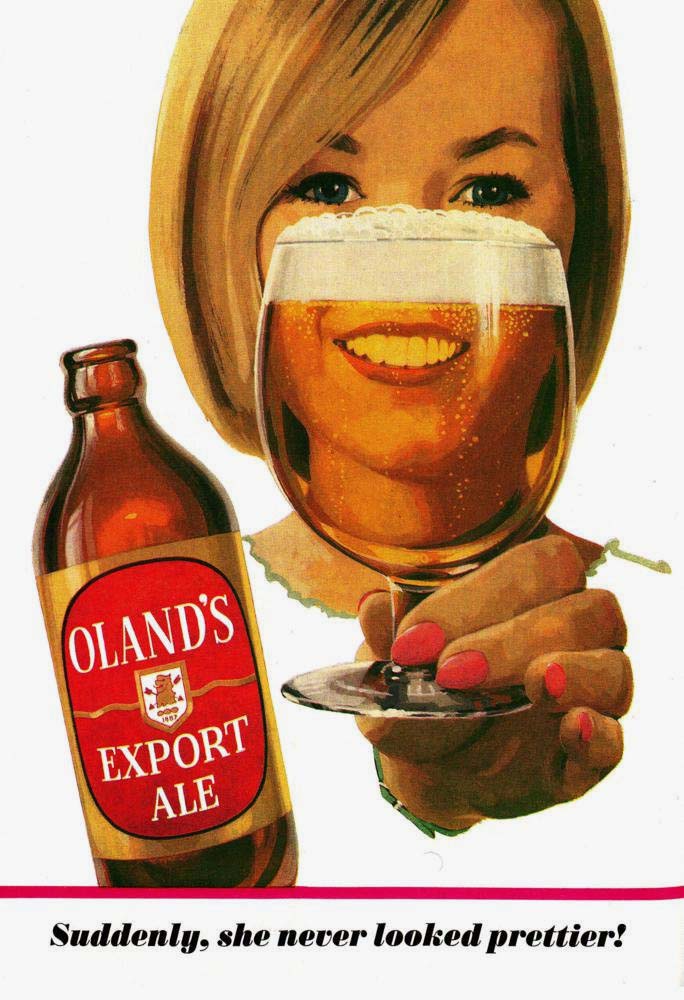

Beer has long churned out sexist and often misogynistic beer labels, going as far back as the early 20th century. Since its inception, beer has excused——if not actively perpetuated——inappropriate behaviour as part of a white male-dominated culture. But as more people come forward with stories of sexual harassment and flagrant sexism, organisations like the Brewers Association and the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) in the UK are finally taking a stand against degrading marketing campaigns.

This history of women being portrayed as objects for the titillation of men is where the rub lies for today’s woke beer drinker when faced with some influencer imagery. But breaking down what individuals find empowering versus what a social group——in influencing’s case, mostly women——may find exploitative is key when diving into the intricacies of the influencer conversation.

“I consent to post these photos of myself,” explains Melis. She knows that showcasing her curves and savvy makeup skills isn’t going to be for everyone. “I understand that there will be some backlash or some negative feedback, and that’s totally fine. You can’t please everyone … but I get to decide what goes out there.”

@thegirlwithbeer

Women are already more likely to be harassed online than men, and that ratio is increasing. Megan and Melis, along with many other women who interact on internet platforms, have numerous horror stories that include online trolls creating cruel memes of them, and strangers showing up at their jobs. They both strategically conceal certain information to minimise these types of encounters.

With that in mind, I wonder: is influencing worth it?

“The craft beer community is a cruel place for women,” sighs Megan. But she admits, “it’s worth it to me because part of my goal is to help other women out in this industry, in general, and especially in production. It’s a goal of mine to help normalise it in a sense.” Melis agrees. “It’s brought me so much more than I had before. I might have a few critics, but I have tens of thousands of people who support me. If I let other people’s opinion of me dictate the way I live, I would have a very unfulfilled and unhappy life. And I really enjoy my life.”

Jen James, aka @pumpedtopour.

I’d rate Megan and Melis’ most brazen content PG-13 at worst, so I feel like it’s a little surprising they get targeted to such a degree. There are plenty of borderline X-rated accounts out there, many of which are run by non-beer professionals. Sifting through hashtags like #boobsandbeer led me down a rabbit hole of over-the-top accounts of women who either aren’t aware of the history of sexualised imagery in beer marketing, or simply don’t care.

Even though I find her ‘Titty Tuesday’ photos to be sleazier than what I personally deem ‘suitable’, her naïve honesty and body confidence are actually kind of inspiring.

Jen James of @pumpedtopour (36.8k followers) is a beer fan and fitness junkie who decided to create an account to celebrate a beverage she loves while showing off her body as “living proof” that people can drink beer and be in shape. She’s vigorously enthusiastic and upfront about the fact that she goes for a wow-factor with her posts. “I get the occasional troll,” she comments breezily. “I honestly don’t pay any attention to it … I simply just block and move on. I have no time for negativity.”

Even though I find her ‘Titty Tuesday’ photos to be sleazier than what I personally deem ‘suitable’, her naïve honesty and body confidence are actually kind of inspiring. Still, her impact on women working in the beer industry is arguably more damaging than she may realise. But if the real problem lies with women reclaiming ownership over their bodies in the light of beer’s toxic history through sexual innuendo of any degree, how can I expect a casual imbiber to even be aware of that?

“There will inevitably be men who see women posing with a beer and devalue their experience and identity as a woman in the beer world, and simply see a body, and objectify them … it’s indicative of existing in a sexist society,” says Waite. She concludes that individuals can only be responsible for what they put into the world, not how the world reacts. “If you want to take a photo of yourself in a bikini enjoying that tallboy of haze and post it on Instagram? You go girl; you do you.”

Abby Fougerousse aka @craftbeermistress

It is possible to garner a following without resorting to overtly sexual content if that’s not your bag. Abby Fougerousse has run the account @craftbeermistress (14.9k follower) since 2011, but switched her personal account to focus on beer in June 2018. Although she doesn’t work in the beer industry, Abby got into craft beer around 2012 and is on a quest to visit every single brewery in Michigan. So far, she estimates she’s been to 192 (“they just keep adding more and more,” she laughs).

As a beer influencer, Abby fits a lot of my definition above. She’s a woman, she’s white, and she takes great photos. But unlike the stereotypical ‘influencer’, she rarely posts photos of herself. “I don’t put pictures of myself in with the beer … [but that] doesn’t mean I’m against it,” she explains. “It makes me sad that so much judgment is being placed on the women with accounts like that (even though there are men who do this too). Everyone should be able to style their account the way they want to and obviously it’s working for them.”

This live-and-let live approach is echoed by Megan and Melis, who say they get lumped in with aggressively sexual influencer content even though they consider their accounts to put beer first, bodies second. But all three women maintain that it’s the quality and quantity of the work that sets them apart.

@isbeeracarb

Even as an outsider to the industry, Abby also hopes her Instagram account will help her explore opportunities and partnerships with breweries. And if not, it’s still fun to meet people and get introduced to different beers. But no matter what, Abby insistently avoids judging others for what they decide to put into the world. “Putting pictures of yourself out there does not hurt other women in the industry and no one should make you feel shame for that,” she says.

Making craft beer a better place for women is not a destination; it’s a journey. I don’t imagine we’ll ever reach the end of that road. But all in all, I’ve come to the conclusion that for all the damage being done to women in beer, it’s not always by women. A sexist culture that’s sustained by generations of male supremacist attitudes isn’t as concrete of a thing to judge compared to a flagrantly sexual photo. It’s always been easier to point the finger at self-assured women rather than confront the systemic inequalities that have gotten us to this point.

At the end of the day, it’s my responsibility to critically analyse context with the images I’m presented with and accept the fact that my truth isn’t going to be universal. The spectrum of opinion and impact is vast and differs for everyone. (Like I said: it’s complicated.) With that in mind, I’m not planning on taking many selfies with my beers in the future. That’s my choice. But to those who choose to do so: cheers.