The colour in Matt Orlando’s tone shifts for the brighter as I ask him about exploring tastes. He’s like a kid discovering the magic of science for the first time. “This is an area that’s extremely interesting to me,” he enthuses, “because the tastes that we’ve explored at Amass, we have done so through texture. Everything we cook there has texture to it, but when you apply those flavours to a liquid form…” He pauses as if his tongue needs to catch up with his brain. “What I’ve learned through this whole process is that liquid carries flavour differently than texture, which is something I hadn’t taken into account before.”

Matt Orlando in the Amass garden. Photo, Mikke Heriba

Orlando talks like a bookish student, fervently soaking up textbook after textbook, passionate about discovery. He is, though, a chef and restaurateur with considerable pedigree. Born in San Diego in 1977, he rose through the ranks of his hometown’s kitchens before moving to New York and eventually landing a position at three Michelin-starred Le Bernardin. That appetite for discovery would see him cross the Atlantic to give his all at a duo of landmark names in the world of gastronomy——Raymond Blanc’s iconic Le Manoir aux Quat’Saisons and Heston Blumenthal’s experimental playground, The Fat Duck——before a chance meeting with René Redzepi saw him head to Copenhagen.

Two years after taking on a sous chef position at Noma and Matt hadn’t added quite enough distinguished names to his CV, thus returning to Manhattan for three years as sous chef at Thomas Keller’s much-lauded three-star Per Se. But the essence of New Nordic cuisine——its minimalist approach to ingredients, its intense synergy with seasonality——had sewn its seeds, and Copenhagen would call again in 2010, a familiar face returning to the then ‘World’s Best Restaurant’ as its first chef de cuisine, before that restless nature sees him realise a personal dream in July 2013; Orlando’s own restaurant Amass (billed as “Copenhagen at its best” by former boss Redzepi) opening in the city’s industrial Refshaleøen.

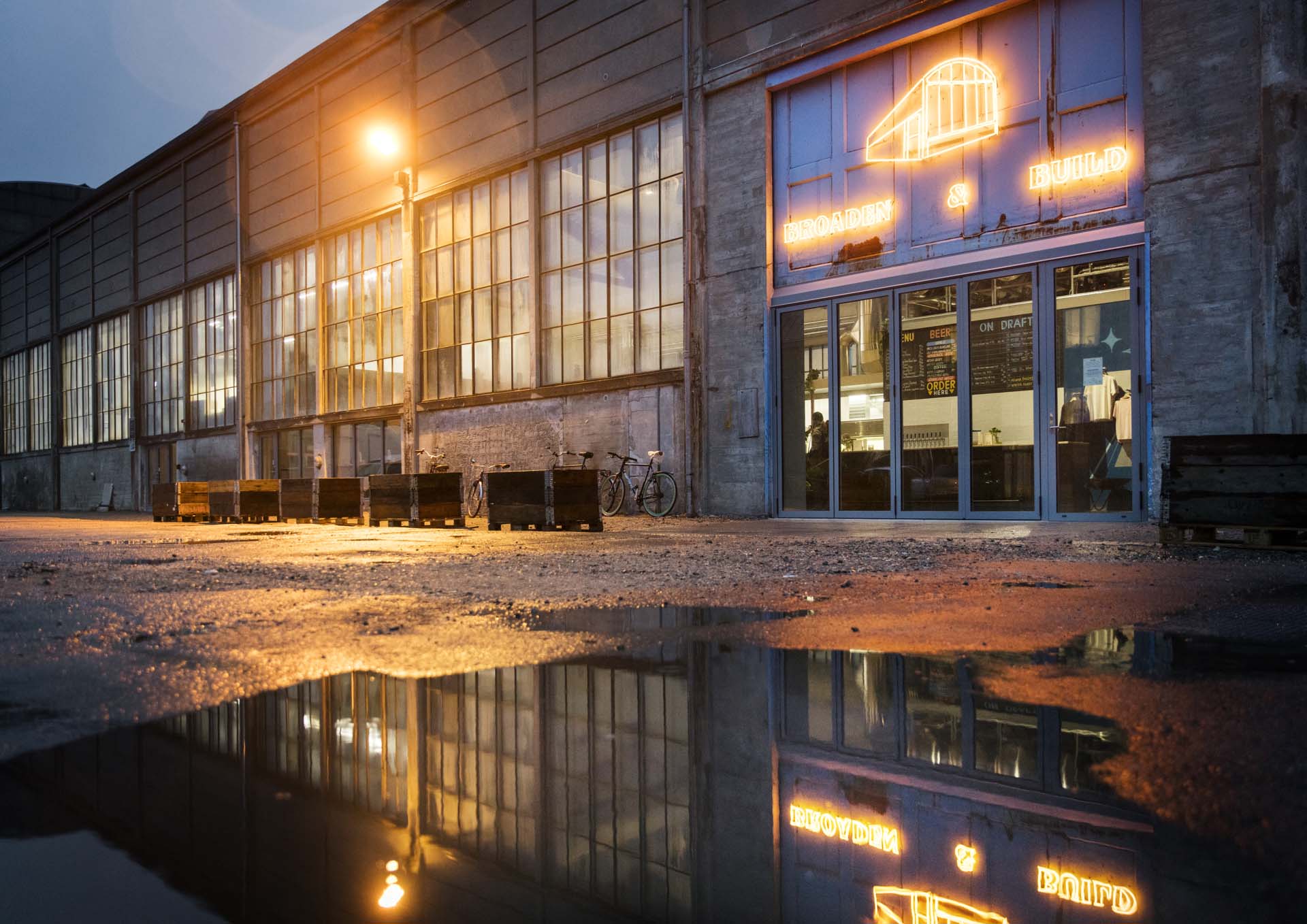

Six years on and the enthusiasm that carried a young chef from one U.S. coast to another is unabated. As eager to explore new frontiers in taste and experience as he was when he decamped to England, Matt Orlando’s latest venture is a sister project to Amass. And that shift from texture to liquid? For his next act, the chef and owner is entering the world of craft beer; Broaden & Build a brewery, casual restaurant, and bar that takes him back to his roots in sunny California.

Broaden & Build Copenhagen

“One of my best friends, Jay,” he begins of his formative years spent amid the San Diego craft beer boom of the early 2000s, “I remember he used to come into the restaurant we worked in, he’d come in at midnight on his days off and set up a whole makeshift brew kit in the kitchen and just brew all night long. That was my first exposure to craft beer, we’d just talk about beer and weird stuff … when you start thinking about beer as a chef before a brewer, you come up with some really abstract thoughts.”

Those abstract thoughts are now conundrums that Broaden & Build head brewer, Tiago Falcone, must translate into their tanks.

“It’s like watching YouTube: you start on one thing and then an hour later you’re watching something completely different.”

“It usually starts with me saying: let’s do ‘this, this and this’, and he’ll sit there rolling his eyes. Almost every time, though, it goes from him saying ‘I don’t know if that’s possible’ into something that is. It’s usually me instigating the idea, bouncing it back and forth, where do we tweak here and there to make it possible, with Tiago saying whether it could be and, if so, what we’ll need to do to make it so. We start with one idea and then in an hour we’ve got a completely different beer style altogether, we keep going off on different tangents. It’s like watching YouTube: you start on one thing and then an hour later you’re watching something completely different.”

Brewing a golden ale infused with elderflower foraged around the local area of Refshaleøen.

And that ‘something completely different’ is exactly what makes Broaden & Build such an exciting project for the craft beer industry. Here is a chef who has been there, done that, has worn the aprons of some of gastronomy’s most lauded restaurants, and created his own. A former head chef of the world’s best restaurant venturing into a world of New England IPAs and pastry stouts. For those excited by taking things to their limits, Orlando’s foray into craft beer is like Radiohead transposing decades of analogue experimentation to the sphere of underground electronic music. It’s a coming together that simply crackles with the excitement of what can be achieved.

After all, Matt is notably unafraid to push his ingredients and flavours to the edge. “It’s a controversial place,” he tells me of Amass, “a place where if you have 100 guests come, two or three will think it’s the worst experience of their lifetime, whilst the others will think it’s the best.” At Broaden & Build the learnings from Amass look set to breathe new life into craft beer; ingredient-focussed beers with the potential to open new portals for a scene that often panders to consumer tastes.

Which takes us back to the subject that awakens the skittish child within.

“When you’re tasting something solid, say a blackened pear [held at 61 degrees Celsius for five weeks while marinating in coffee grounds] that we just brewed a stout with, it’s quite chewy and that flavour——how it moves around your mouth——is very different from when you take that pear and you make a super intense tincture with it and drink it. When you say ‘I wanna make a blackened pear stout’, it’s about taking that pear, putting it in a liquid form, tasting it, and then seeing if it’s still something we want to use. And if we do, do we need to use more than we thought originally, or is the flavour what we wanted now it’s in liquid form?”

Tasting through unconventional ingredients from the Amass pantry.

Lacto-fermented rhubarb, fresh beetroot juice and pulp for the gose, Inoculate.

Using the meat grinder to process 100 kilos of the season’s first green gooseberries to be added to a double IPA.

“That transfer of flavour from solid to liquid for a chef is super interesting, because in doing that, you may be able to revert it back into the kitchen at Amass or at Broaden & Build and say: ‘we’ve always used this in solid form but we’ve tried it as a liquid and it’s actually much better’. It’s a process that gives us something to explore the next time we cook something.”

For fans of food and beer, these flavour explorations are something to relish. Broaden & Build has already turned out a kvass brewed with surplus bread and fermented with sourdough starter from local bakery Lille, which was infused with leftover lemon, bergamot, and grapefruit skins——“it tastes like a natural wine, super interesting,” he enthuses——and a low-ABV gose with lactic from beetroot and rhubarb. Recent releases include a sour with sea buckthorn and mugwort, and an ‘imperial frappé stout’ with house-made roasted parsnip and coffee caramel. “If you’re looking to drink a big hazy juice bomb of an IPA, those are not the beers you want to order.”

“We have a couple of big IPAs that are going to come on just to please the kids out there, but we also have a lot of IPAs that are hazy but not overly sweet or that have so many hops in that there’s hop burn. Which is a difficult story to tell right now.”

Naturally, Matt wants Broaden & Build to produce beers that can accompany food, and as such, drinkability is of prime concern. “Beers that sit somewhere between 5—6.5% like pale ales, Kölsches, saisons and stuff like that … we’re trying to focus on really drinkable beers, because if you want to do this whole food and beer thing, those big juice bomb IPAs really just overpower the food. So, we’re not saying we won’t have some around, but we’re trying to focus on integrating beer into food and if you have a really aggressive hop profile it’s really hard to get other flavours into that beer without the hops dominating.”

Sanguine, a DDH DIPA brewed with 300 kilos of biodynamic blood oranges from Salamita, a farm in Sicily.

Which brings us to the dank, resinous elephant in the room.

“Of course we are brewing IPAs, we have a couple of big IPAs that are going to come on just to please the kids out there, we also have a lot of IPAs that are hazy but not, like, overly sweet, or that have so many hops in that there’s hop burn. Which is a difficult story to tell right now, because this market is so focussed on these super hazed-out IPAs … however, we’re also finding it fun to look at them and say: ‘OK, how can we make this different?’” The exuberant experimentalist returns. “We just brewed this massive IPA with 300 kilos of blood oranges in it just to stand up to the hops,” he proudly proffers.

Indeed it is big——7.5%——it has a creamy mouthfeel, and it is definitely hazy. Just don’t call it a NEIPA. “If you label it as NEIPA then it better be that, we found out the hard way. We were brewing these hazy pale ales and hazy IPAs but we were brewing them to be drinkable as well, and we just got bashed at the beginning for that, because as soon as you put hazy or NE in front of it, then people have a certain perception of what that is. So even though we’re brewing pale ales that have a bit of haze in them, we’re just calling them pale ales, because as soon as people see those words they’re thinking this is going to be a juice bomb that blows my face off .. that’s a lesson we learned at the beginning.”

Back at Amass, it is said that René Redzepi once told Matt that by adding tablecloths he could get a Michelin star or two, but thanks to an upbringing spent surfing and skating in San Diego, the conservatism of European fine dining does not appeal. His is a restaurant of stark industrialism, graffiti on the walls, hip hop on the stereo. And Broaden & Build follows suit. Matt Orlando doesn’t follow rules, he writes them; something this is particularly true in his extreme approach to sustainability.

“When we built the brewery, because we have a lot of space there, I wanted to take this opportunity to create a research kitchen just focussed on by-products and techniques, and very focussed on spent beer mash. We’ve done some really cool things with it, and have been able to turn it into chocolate bars that contains no chocolate, misos, soy sauce style sauces … we also work with a company that takes all the mash (at the present time we can’t process it all) put it through a fermentation process, trap the methane, turn it into biofuel and then we run the whole brewery off that, one quarter of the CO2 emissions that electricity produces.”

The Broaden & Build team foraging for wild rose petals to be added to gose, Inoculate.

“From my own experience, where the restaurant industry is in relation to where a product comes from, traceability, and things like that … the beer industry is not as far along. It’s not so much talked about in the brewing world, I don’t think it’s seen as cool, and so for us——whether it’s at Amass or Broaden & Build——I think the bigger picture is to try things that have maybe not been tried before in regards to sustainability. Hopefully if people see it, they may go back to their brewery and say ‘hey it’s not actually that hard to do’. Hopefully we can set an example of how you can do things.”

Making a serious effort with sustainability and ingredient experimentation can go hand-in-hand, and so food-orientated brews should surely be a natural progression for the craft beer world? “There are some brewers starting to do interesting things and really starting to take the angle on food,” he adds, “or at least looking at food products as something interesting to use in beer. Jean [Broillet] at Tired Hands is doing crazy stuff, super interesting, I’ve become good friends with him. I was in in Philly for a chef’s conference and I just called him up, I was lucky enough to spend two days at the brewery with him, talking about their process, how they’re approaching beer and how the whole operation works. They’re focussing on local farmers’ ingredients, local stouts, things I don’t think many people are doing.”

Deeply committed to locality and sustainability, a 600 square foot urban farm is situated in direct view of Amass’s main dining room, boasting some 80 different varietals of plants that appear on their daily menu. Photo, Mikkel Heriba.

“Also Fonta Flora are doing some really cool stuff, and of course Jester King have their own little universe out there. I was down there a couple of years ago, in the middle of nowhere where they have this little farm where they’re getting animals creating all their own grains, what they’re doing out there is nuts, they’re really taking it to the next level. They pretty much just focus on sours so they’re really harvesting the local terroir … it’s still few and far between, but in my short time in the beer industry, locality and such is being talked about more.”

And few places have such focus on locality as Amass; and now by proxy Broaden & Build. As well as local farmers and regional purveyors driving the former’s constantly-shifting tasting menu, there is a 600 square foot urban farm situated in direct view of its main dining room. B&B will take advantage of the same products and suppliers as well as feed off its scraps. It will place the same emphasis on responsibility and on up-cycling by-products. It will adopt its same stringent mindset, and its R&D kitchen will help push both in new directions. What it won’t do, however, is provoke its customers in quite the same way.

“It’s just a more casual place,” Matt says of his new project. “On the day of opening I was unnervingly calm about it and people were, like, ‘you seem so calm’, and I came to the realisation that I’ve been solely operating a place that nudges people out of their comfort zone for the last five-and-a-half years. Every time I go into service at Amass, I have this somewhat nervousness in the back head saying: ‘alright, who’s not going to like it tonight’, someone who doesn’t quite get what we’re doing,” he laughs. “Opening a brewery is something different: beer is such a communal thing, and the food we’re doing there——whilst in the same sort of concept of Amass——is super approachable and casual. Not many things on the menu are going to be challenging for people in a flavour sense, and the beers are accessible, too. That stress of who’s not going to like it tonight isn’t there.”

Broaden & Build’s interiors owe much to Amass’s uncompromising aesthetic.

Whilst Broaden & Build shares a similar aesthetic and approach to Amass, that accessibility means many more will get to experience Orlando’s vision than before, and the bar is already attracting its regular crowd. “Where we are there’s not really much residential but there’s a lot of businesses, so we get that crowd, local people that work here and stop by on their way home … stop at the bar and have a couple of beers, which is nice.” Approachable yes, but Matt sounds instinctively eager to take his drinkers to the next level; if not a tad apprehensive. “I hope that we can at least open their eyes,” he says of the potential to educate his customers. “Of course you can come in and just sit at the bar and drink beers, we encourage that, but the beers are geared towards food and that’s a hard story to tell.”

Increasingly, though. Little by little. Beer drinkers are looking for the stories within. Traceability, locality, innovation and creativity … storytelling is permeating into craft beer culture in the same way it did gastronomy. Next for Broaden & Build? More stories, however hard to tell. Focussing on barrels that come from natural wine producers that supply Amass, the brewery are currently undertaking what Matt calls a “pretty aggressive barrel ageing programme”; which has begun with a Tired Hands collaboration putting a 500-litre Chenin blanc barrel (from Château de Passavant in the Loire Valley of France) to use.

In Broaden & Build, Matt has realised what he describes as ‘a lifelong dream’. It may not be the first time a chef has explored how their perspective can be applied to beer-making, but it is categorically the first time a chef of such calibre has done so. It is another new brewery. Yes. But more importantly it is the addition of a new mindset to a rapidly growing industry. Food- and sustainability-forward, Orlando’s approach is a model capable of shaping craft beer’s future.